|

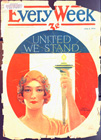

Every Week3 ¢Published Weekly by Every Week Corporation,95 Madison Avenue, New York© July 3, 1916UNITED WE STAND |

By WALT MASON

[photograph]

John P. Johnson lost both hands in a railroad wreck, but that doesn't hinder him now from earning a big income with his fish business.

CONSPICUOUS for pluck he stands, the handy man who has no hands.

This John P. Johnson is a Swede, and "keep things humping" is his creed. He came to our star-spangled shore some twenty years ago, or more. Here, in a railway accident, his frame was badly crushed and bent. He lost both hands, and well might he sit down and weep for poor John P. But John was not the weeping sort; he was a hero and a sport.

And scarcely had he left his bed, ere he went forth with jaunty tread, to seek the work his soul desired, and as night watchman he was hired. And as he paced along the piers where Beverly her masts uprears, he planned for bigger, broader things. The spirit of this man had wings.

He built a house-boat, where he dwells as happy as your wedding bells. Upon the stump of his left wing he has a hook, and he can sling that hook around and do his chores as well as any man indoors.

At first, to help to pay the freight, he did some business selling bait; he handled fish-bait by the ton, and bought a dory with the mon. And then he put more bait on sale, and bought more dories with the kale, and now he has a string of boats, as smooth as anything that floats, and lets them out to gents who wish to rake the briny deep for fish.

Then Yonny Yohnson sat him down, and said, "Why not sell fish in town?" No sooner thought of than 'twas done, and this brought in new brands of mon. And ever thus the trade expands of this brave man who has no hands. His busy boats lie, rank on rank; he has his bundle in the bank.

I USED to be a bookkeeper. Now I am married and have two children, one five years old and the other two. I could not leave them to go out to work, but I found it hard to reconcile myself to the thought that I was adding nothing to the family income. Then, one day, this plan occurred to me: I had been spending nearly every afternoon taking my children out to walk and to play games. One day I offered to take a neighbor's child with me, and this gave me the idea of starting and informal day nursery.

I charge 25 cents for taking charge of [?] child for three hours at a time. When [?] mother wants to leave one of her children with me for the day, so that she can take a long trip, I charge 25 cents for the morning, 25 cents for dinner and 25 cents for the afternoon.

Of course, one has to be fond of children to do this kind of work successfully; but for a mother who already has one or two little children to look after, five or six more make very little extra trouble. I often earn from two to three dollars a week in this way. I am careful to see that the children are kept busy all the time. I teach them simple games: and in warm weather I have a box of sea sand on the piazza for them to play in. In general I take children form two to six years of age, but sometimes I take care of little babies in order to give the mother a day off.

Mr. WILLIAM LOOMIS of Parsons, Kansas, had an idea. All Parsons-ites agrees that there was no other town in the United States that could compare with Parsons; but Mr. Loomis, as Commissioner of Streets, was not blind to the fact that even Parsons could be improved. For instance, there were many vacant lots in the town where gaunt, unseemly weeds thrived, waxed, and grew strong in the manner of weeds.

Mr. Loomis looked long on the weeds. And then came the idea.

He would grow potatoes on the lots. Almost all the inhabitants in Parsons were fond of potatoes. Parsons itself would grow the potatoes. Next week the city commissioners authorized hi to conduct a municipal potato patch, utilizing all of the sixty vacant lots.

Parsons is enterprising. soon it will grow lettuce, turnips, peas—all that is needed for the salads of the prisoners in the jail of Parsons, who now are weeding instead of breaking stone. Mr. Loomis [?] soon to persuade the city to buy [?] seed and give it to the poor to [?] This would be cheaper than pay- [?] have the weeds cut.

[?] will be no weeds in Parsons.

[photograph]

BEFORE golf on Fourth of July morning, before fire-crackers, before breakfast, should come a few minutes of quiet Thought.

And the Thought should be something like this:

I am proud to-day that I am an American.

I am proud that, after so many thousand years of struggle by men against their kings, there should have been founded a new government in the world, kingless, with no ruler but the vote of its subjects, with no oppression save the oppression that he ignorance or selfishness or foolishness of men visit upon themselves.

I am proud that is should have been in my country, and not in some other, that those words were written and signed one hundred and forty years ago to-day:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.I am proud that—stumblingly, to be sure, and with judgements often faulty—my country has nevertheless held close to that ideal.

I am proud that across her threshold millions of men and women of other lands have come, to find here fuller freedom, better homes, larger opportunity. And that their pilgrimage has not brought them disappointment.

I am proud that neither they nor I can be bidden by any man to worship God in any way except as our consciences may dictate; nor deprived of liberty or advancement or public honor because of our creed.

I am proud to live in a country where Abraham Lincoln, born in a hut, with talents fit for a palace, could win his way to the palace instead of being chained for life to the hut.

I am proud to live in a country where every factory, office, and business block, every legislature, every bank and university, every pulpit and bench, bears testimony that neither poverty nor race nor circumstance bars intelligence and industry from the rewards of success.

I am proud to live in a country that, having had placed in its trust a priceless empire like Cuba, could restore that empire to its own people, crowned with new liberty and security and health.

With humble gratitude I recall to-day that none of these blessings of which I am so proud have come to me by my own effort; that every one of them is the gift of brave men, and is stained with brave men's blood.

And so, reverently and earnestly, I pledge myself that the spirit of the men who founded this nation shall not die out in me, nor in my household;

That I and the children who are mine shall consecrate ourselves to the task of passing on unsullied the trust delivered to our hands;

That this nation shall continue to be, what it was founded to be, and inspiration and an example to the nations of the world.

And that if, in the maintenance of this ideal, there shall ever come a day when this nation will demand of me what it once demanded of Washington and Jackson and Lincoln, I shall not be found unworthy of their memory.

Bruce Barton, Editor.By B. C. FORBES

AMERICA'S big men are learning to play.

Our business gladiators are finding that he worketh best who playeth best.

Labor has demonstrated that workmen do as much in an eight-hour day as they used to do in ten hours.

Capitalists have made a similar discovery nearer home.

"Unless a man has learned how to relax before he is in his fifties, he finds the hardest work he must do is to take relaxation," declared Frank A. Vanderlip, president of America's largest national bank, in discussing the subject of this article. "A great many men do not know how to drop business from their minds and really enjoy recreation. To accomplish great work, relaxation of some sort is about as necessary as work."

The late J. P. Morgan's example influenced many financiers to neglect exercise and to overwork. Mr. Morgan never walked a block if he could avoid it; ate sumptuously; smoked his famous black cigars from morning till night; and worked at tremendous pressure. The doctors once took him in hand and forced him to begin living like a normal human being. But the experiment threatened to end fatally, so the financier returned to his old habits, recovered quickly, and—outlived his doctors.

"Why don't you retire, Mr. Morgan?" a friend once asked the aged banker.

"When did your father retire?" countered Morgan.

"Oh, in 1900."

"And when did he die?"

"In—in 1901."

"Umph!" growled J. P. "If he'd gone on working he'd been living yet."

But Harriman's death struck terror into many a high financier's heart. The railroad wizard made a million dollars a month in his later years—but at the cost of his life. This epitaph could truthfully have been inscribed on his tombstone:

EDWARD H. HARRIMAN

Aged 61 years

He committed hari-kari by overwork

Since then there has been a boom in millionaires' clubs; a greater number of inoffensive wild ducks have been shot; more trout, salmon, and tarpon have been hooked; the demand for saddle horses has increased; the consumption of high-grade sole leather has gone up; the opera and theaters have been better attended; and—whisper it—poker problems have often of an evening displaced serious business problems.

My little investigation into the diverse means the nation's foremost men of affairs employ to drive business cares from their minds reveals, among other things, that no matter how many millions a man may possess, how many thousands of workmen he employs, or how perplexing his difficulties, he often remains just an overgrown boy.

Take the greatest railroad man who ever lived—James J. Hill. He played with picture blocks—the things you see children trying to arrange to form a cow or a house or a boat. Only, the man who built more railroads than any other American used the most difficult sets the makers could devise.

"I was invited to Mr. Hill's New York home for dinner one evening," one of his friends once told me; "but Mr. Hill had started to piece together an elaborate landscape with his picture blocks, and nobody could coax or cajole him to stop for dinner. Finally, after the butler had made several entreaties, Mr. Hill tore himself away long enough to dine—but he immediately excused himself, left his guests, and returned to his puzzle. When we left, at ten o'clock, there were still holes in that landscape which Mr. Hill was determined to fill before going to bed."

MR. HILL also played solitaire by the hour.

Solitaire, I have discovered, is the favorite card game of many old-school financial and industrial leaders.

The late J. P. Morgan's solitaire table, folded until it resembled a suit-case, traveled with him everywhere, abroad and at home, on land and on his yacht. The first thing unpacked always was this little table. And when the financier sat down to play, no member of his entourage would disturb him, were the heavens—or U. S. Steel common—to fall.

"On the Corsair," said one of his cronies to me, "Mr. Morgan would play solitaire from dinner-time to bed-time without once passing a remark to the guests moving about the deck. I rather believe, however, that he was accustomed to do serious thinking at such times—that he pondered problems not of the card-table."

Theodore N. Vail, the creator of America's unequaled telephone system, the man who has done more than any other human being to put on speaking terms distant people, is a solitaire devotee. Also, he can become enthusiastic over children's mechanical toys. He often amuses himself with them the greater part of an evening. Opera and theaters are his other indoor sports. Horses are his out- of-door hobby. For many years he has bred fine ones, and only recently he presented a large part of his summer farm to the State of Vermont.

"I'm kind of funny, I suppose," said E. H. Gary, head of the U. S. Steel Corporation's army of more than 250,000 men, when I asked him what he did to keep in fettle. "I don't play golf—that takes too much time. I don't play cards—because I don't care for gambling. And I don't dance—I'm probably too clumsy.

"I walk a lot. Almost every morning I walk from my house in Fifth Avenue across Central Park, up hill and down dale, to the Elevated, a distance of perhaps three quarters of a mile. I do the same thing going home. And, as you know," Judge Gary added, smiling, "I do a good deal of walking here."

We were in Judge Gary's office. When he becomes interested in a subject, especially if it be reminiscent, the Judge, his thumbs stuck in the arm-holes of his vest, paces up and down the floor, stopping only occasionally to emphasize a point or ask a question.

After napping or resting for an hour or more before dinner, Judge Gary very frequently goes out to the theater, the opera, or parties—Mrs. Gary is a noted entertainer.

BICYCLING is the pet sport of Jacob H. Schiff, the veteran head of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., the most powerful rivals of J. P. Morgan & Co. At his summer home in Bar Harbor he may be seen on his wheel every day. In the city he walks.

"But what about the winter-time?" I asked his son, Mortimer L. Schiff.

"Attending charity meetings seems to be his principal diversion in the winter," was the smiling reply.

James Stillman, chief owner and dynamic upbuilder of the National City Bank before he made Mr. Vanderlip president, took up bicycling in the olden days and has stuck to it since. Mr. Stillman in recent years has spent about six months of every twelve in France.

"I have now learned the art of living," he told me, when I asked him what lesson Harriman's death conveyed to other men immersed in momentous affairs. Mr. Stillman indicated that John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie were wise old owls to quit the money mart for the golf links.

MR. VANDERLIP does more work than half a dozen ordinary mortals. He keeps a string of secretaries busy; his office is besieged all day by visitors and the higher bank employees—there are thirteen vice-presidents. He is the active financial head not only of the City Bank but of the new $50,000,000 American International Corporation, the new $70,000,000 Midvale Steel and Ordnance Company, and the International Banking Corporation.

"My hobby is building—the creation of something that will stand after you have gone," said Mr. Vanderlip. "I love architecture. It is a keen pleasure to me to plan a building, to work with an architect, to see the picture evolved into a finished, concrete thing.

"Swimming is my special relaxation—we have a pool at our home (in Scarborough). I also enjoy doing carpenter work with the children. Then, we go in for riding. All my six children are not old enough to ride, but enough can to make quite a cavalcade! I would not live in the city," Mr. Vanderlip added with emphasis.

"Don't take yourself too seriously and you have no trouble in relaxing." That was the maxim laid down by Charles H. Sabin, ex-farm-boy and now president of the Guaranty Trust Company, the largest in the United States, who, report says, first attracted attention by his ability to play.

While a youth in Albany, Sabin distinguished himself as a football-player and as a baseball pitcher. Being from the farm, he knew also how to ride. So he easily made his mark at polo. Certain influential financial gentlemen were glad to have him come to New York, and Sabin became star player in America's crack polo team.

"Work is fun," Mr. Sabin went on. "A good many men take themselves far too seriously. Swell-headedness is fatal.

"I am too stout to play polo now, but I play at golf. And—I like a game of poker."

Charlie Sabin is described by his friends as "a regular fellow." His success in upbuilding the foremost trust company in America has not spoiled him.

I have often been struck with the fact that seldom are the nation's greatest doers out of their homes in the evenings. As a morning newspaper man, I have had

[illustration]

"On the 'Corsair,' the late J. Pierpont Morgan would play solitaire from dinner-time to bed-time. I believe he thought out serious problems at such times."

Curiously, the morning habits of the presidents of the two greatest organizations in the world, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the U. S. Steel Corporation, are almost exactly alike. Both get up between six and seven, breakfast early, look over the newspapers, and stroll around their estates before starting for work.

Samuel Rea, of the "Pennsy," however, is a land-lubber, while James A. Farrell is a sailorman.

Mr. Rea's hobby is collecting Chinese porcelain and antique silver. So deeply has he studied that he can now translate the ancient hieroglyphics on specimens.

Mr. Farrell, the son of a skipper, is an inveterate sailor. Until very recently his boats were always of the sail variety; but last year he condescended to use a steam yacht. Incidentally, it was Farrell's boyhood voyaging that won him his present job, for he then began to gather knowledge of foreign ports, a knowledge that is to-day unmatched by that of any deep-sea captain. He not only knows the ports,—the depths of the water at each, their quay space, their customs charges, etc.,—but he knows conditions in the interior of every land on the globe. Not one worth-while book is published about foreign countries that Farrell does not buy and read. Mainly through his efforts, the Steel Corporation has sold $100,000,000 worth of steel products annually to foreigners.

JAMES SPEYER rides horses in the city, but he gets more fun out of his country home, near Ossining. The last time I was there, he proudly pointed to some painting work he had done in the gardens, and offered to bet that the village painter could not have blended the colors to harmonize better with the surrounding foliage.

J.P. Morgan's main diversion is yachting. He can handle a sail-boat with the consummate skill of a Nelson. Mr. Morgan is not a glutton for work; he contrives to spend considerable time with his family, although since the war began he has been kept going at high pressure. He is not money-mad.

Henry P. Davison, Mr. Morgan's right-hand partner, prefers horseback riding to yachting, although he is a bit of a salt. President Smith of the New York Central also is a rider.

Art claims much of Otto H. Kahn's time when he is not drafting railroad reorganization plans, putting through big financial deals, or wrestling with other problems that international bankers have to solve. He is president of the Metropolitan Opera; he was the moving spirit in starting the Century Theater; he is a violin-player of no mediocre order; he is as keen a judge of painting as of music, and does far more than is known to encourage native artistic talent. He has a private golf course on his Morristown, New Jersey, estate. Also, he has taken ribbons with his horses. So, in one way or another, he manages to sandwich a little pleasure into business.

Newton Carlton, president of the Western Union, indulges in the cheerful avocation of collecting relics of Egyptian mummies. Anything under a few thousand years of age does not interest him. He has spent many months in the land of the Pharaohs and is quite an Egyptologist.

Daniel Willard, president of the Baltimore & Ohio, whom the Eastern railroads chose to lead their fight for higher freight rates because of his superhuman energy, detailed knowledge, and innate diplomacy, modestly replied, when I quizzed him: "I read a lot and play golf a little."

I can add, however, that when things become trying, as they sometimes have during the last six years, in which Mr. Willard has supervised extraordinary expenditures of $110,000,000, he finds solace in playing the violin.

Charles M. Schwab has, in his Riverside palace, the finest private organ in New York. He often relaxes by playing it. The story is told, you know, that it was the boy Schwab's piano-playing that first won him the recognition of Andrew Carnegie. Mr. Schwab, when he is not scampering over the seven seas booking gigantic contracts for his Bethlehem Steel Company, likes to invite a few of his neighbors in for a game of cards.

Our financial and industrial Samsons are working doubly hard to-day. But they are enjoying it—they are reveling in it.

H. H. Rogers, the late Standard Oil magnate, complained, about the time the muckrakers and the demagogic politicians held the stage, that "the spirit of enterprise has been killed." This "spirit of enterprise" has been re-born.

FIVE years ago a great figure in American finance said to me:

"I am sick of it all. The whole atmosphere is against business. We breathe antagonism. It stifles you. You feel repressed and depressed. You simply can't go ahead and do things. I hope shortly to retire."

Contrast that with this, enunciated the other day by the same financier: "The people are with us now. They want to see the United States conquer fresh commercial fields. They applaud new enterprises, especially those designed to strengthen us on the seas and in the world's markets. It is now a pleasure to work."

This buoyant, enthusiastic feeling is general. Few financiers have had long vacations since July 31, 1914. But the consciousness that they are swimming with the tide of public opinion, not against it, buoys them up and braces them up.

They can both work and play with keener zest.

It is a happy augury for the future of the U.S.A.

By HOLWORTHY HALL

Illustrations by Frederic Dorr Steele

MY friend Tilson had written another play—of course, everybody's doing it nowadays, but Tilson was a man in a thousand: he had a contract. He wrote this play: and after it had been sufficiently doctored, and the locale changed so as to fit the scenery of a recent failure and thereby save overhead expenses, a cast was persuaded to leave Belasco's door-step, and the rehearsals began.

Tilson took me to see one of them. We traveled up Third Avenue until we came to a building devoted chiefly to employment agencies and Zahnarzten, and on a lower floor we found a very large, very dim room, extremely well heated by steam and not ventilated at all. In the immediate foreground there were disconsolate individuals engaged in destructive criticism; in the middle distance there were men in shirt-sleeves; farthest north there was a low platform strictly Elizabethan in its appointments, which comprised half a dozen common kitchen chairs and a dilapidated park bench resting against the stained brick wall at the extreme rear.

On this quasi-stage a pretty girl and a diffident young man faced each other. Something in the girl's manner caught my attention; I suddenly realized that I was staring at no less a personage than Dorothy Dunn.

"Thunder!" I said to Tilson. "Why didn't you tell me she's in it? Now it's sure to get over."

"Not necessarily," he denied, frowning. "Watch that man Kelly opposite—this is the big love scene in the second act."

Up on the stage, the most popular inégnue of the season was regarding Kelly from the deep ambush of her eyelashes.

"Really, don't you know it?" she breathed. "Shall I play it for you?"

"Please do," said Kelly, stifling a yawn; and Miss Dunn obligingly seated herself on a kitchen chair before the park bench, and played it for him.

"'A Little Love, a Little Kiss!'" whispered Tilson in my ear. "She does it mighty cleverly on the piano—if we only had a decent juvenile!"

"Why don't you get one?" I asked him.

"Look! Look at that!" he groaned, plucking at my sleeve.

Kelly had approached Miss Dunn: he stood over her; she raised her head ever so slightly; he accepted the tacit invitation. One of the men in shirt-sleeves scrambled up on the platform.

"Here! Hold on! Wait a minute!" he snapped. "Kelly—won't you please remember your character? Cut out that hocum! You're a young devil, you are—you're full of vim, vigor, and vitality! Shoot some hop in it! All over again—come on, now! Start something!"

SO we gazed intently until the blasé youth had kissed Dorothy Dunn some six or eight times; and then Tilson gripped me firmly by the arm and escorted me out of the hall, and down to a near-by restaurant, where he ordered refreshments for two and swept me into his confidence.

"For one solid year," he said savagely, "I worked on that play! It's good—I know it's good; and Dunn's a marvel. And then they hand me a cold-blooded fish like Kelly! He isn't simply murdering the part—he's doing it by slow torture. Why, the whole point of the thing is delicacy and sentiment! If that doesn't get across, we might as well get some rapid-fire comedians and a couple of sidewalk conversationalists and an orchestra leader, and make it a nigger act! The big stiff! You'd think he never made love to a girl in his life! It's terrible—"

"It's curious, too," I said. "I should think any normal citizen could work up a little excitement over D. Dunn."

"That isn't it! He's a rotten actor."

"Why not replace him, then?"

Tilson shrugged his shoulders.

"It can't be done. That's one of the barriers in this business."

"But, no matter how bad an actor he may be," I said, "I don't see how he can help projecting some realism into a situation like the one we've just seen. I couldn't."

"My dear fellow," said Tilson pityingly, "you didn't expect to observe any genuine emotions floating around the stage, did you?"

"Why not?"

"It doesn't happen; that's why."

"Oh, not in general. But, in particular, I can't quite comprehend how Kelly, or anybody else, could rehearse that bit of business very many times without doing it rather cheerfully. The effect—"

"But there isn't any effect," he persisted. "There simply isn't any! Making love on the stage is nothing but one phase of the job. These people could do it forever, and it wouldn't have an effect worth mentioning."

"Well," I said, "you'd probably argue, on the same analogy, that a professional wine-taster doesn't get an effect from vintaged champagnes, since tasting is nothing but a part of his job. But I maintain that if he repeats the identical experiment—"

"You assume that a man who kisses Dunn often enough ought to fall in love with her anyway?"

"It seems to me inevitable."

"But actors almost never—" He stopped and grinned reminiscently. "Well, hardly ever," he corrected. "I do remember one instance when your theory worked out."

"Go ahead," I told him. "I might get a story out of it."

Thus Tilson:

IT was about a year after I'd taken the desperate plunge. I'd resigned from the bank to use a pen as a crutch instead of a cane. I'd had one Broadway production that ran three consecutive nights, and I'd done some short stuff for vaudeville, and a lot of one-act pieces for society amateurs. I had an office so small that every time I took a long breath it made a vacuum; but I had some wonderful embossed stationery, and that was a comfort.

I was sitting in the office one morning, getting ready to stall the rent while I wrote the great American drama, when some one knocked very gently and politely on the door. Instinct advised me that a beautiful, pathetic, trembling widow was about to cry on the rug as she showed me where to sign for the twelve illustrated volumes of the world's best poetry. I'd been there before.

But I said: "Come in!" and went on writing.

The door opened softly. Presently I put on the fiercest expression I had, and turned to quell the proud invader. I didn't believe that any widowed book-agent could remember her patter after she saw that look of mine; and it was immaterial to me whether her game was to send Willie through college, or to lift the mortgage, or to support herself, now that her husband—invariably the president of a large corporation, and a man who carelessly lived up to his income—had died not more than twenty-four hours after his insurance lapsed. In fact, I was willing to borrow money from her. I had to.

You may consider my amazement when a young man six feet tall and forty inches around the waist entered. He had on his third-act clothes, with a silk hat and absolutely pure spats, and he was prodding the rug with a rosewood cane.

"Mr. Tilson?" he inquired, removing one glove, and instantly putting it back.

"Right," I said. "What can I do for you?"

He placed his hat on the floor, balanced the cane on it, and drew off the left-hand glove.

"Unless I'm mistaken," he said haltingly, "you—you wrote a children's play for—well, for some friends of mine in Tarrytown."

"Right again!" I said.

"And they were—well, they were so thoroughly satisfied—at least, I infer that they were satisfied—"

"Just a moment," I interrupted. The young man grew fiery red, and hastily hauled on his glove. "I don't want you to labor under a misapprehension. Your friends may have been satisfied, but I wasn't."

"Indeed!" He glanced at the door, hesitated, and slowly stripped his left

"Not for me, it isn't," I said. "Your friends wanted something rather like 'Peter Pan,' only better and more up-to-date, and they thought I'd get such a reputation by associating myself with them that I wouldn't expect any payment in cash. Won't you take off your gloves?"

"Thank you," he said, following my advice, and utilizing the hat for storage purposes. "I dare say we shall have no—well, no quarrel as to financial arrangements. Perhaps you know the town—the suburb called Kenilworth?"

"I've heard of it."

"At present," said the young man, peering over the top of my head, flushing, and diving abruptly for his gloves—"at present I have a little estate—my address is merely Kenilworth, New York-well, I live there! My name—"

"Yes?"

"It's here somewhere," he said, fumbling. "Ah! Permit me." He gave me a card, and began to fit his thumb to its gray shroud.

"Let me put them over here," I said; and I took the gloves away from him and deposited them out of his reach, whereupon he began to jiggle his watch-chain. "Mr. Throckmorton."

"Yes," he said. "Well, I understood that you wrote plays for amateurs. The average amateur play is—you know what it is yourself."

"I ought to," I admitted.

"And in Kenilworth an amateur play is given each year for—well, for charity. They're usually quite bad."

"You interest me strangely," I said; but his nervousness was beyond even that palpable intimation.

"So it—well, it occurred to me," he went on, looking hungrily at his gloves, "that you—you might—"

"I'll be glad to do what I can, Mr. Throckmorton."

"But there are certain requirements. Would you object if I smoked?"

"I'm sorry I haven't a cigarette to offer you."

"But I never use them. May I offer you a cigar?"

When we resumed the discussion through a film of smoke, he was infinitely more at ease.

"The fact is, Mr. Tilson," he said, "I want something—romantic. There must be plenty of—well, love episodes."

"A laugh in every line, a clinch every five minutes, and a punch all the way through," I suggested; "with a well sustained plot and good dramatic action. You've come to the right office. That's my specialty."

"You understand—nothing delights an audience in a play of this sort as much as—"

"I understand perfectly," I said. "All amateurs want to kiss somebody on the stage. It always goes big. I'll look out for it."

"And then I should want you to come up to Kenilworth to manage—well, to direct the play."

"Certainly. And you're to play the lead, I take it."

Mr. Throckmorton became the color of ancient burgundy, and perspiration gleamed on his forehead. He surreptitiously reached for his cane, and held it tightly.

"Why, no," he said. "I—the fact is, I have commented upon the last few plays so—well, so adversely—that in this case—it's quite extraordinary, I dare say, but I'm afraid I shall have to appear—as the author!"

I had to laugh at his embarrassment.

"That's simple enough. I've written a number of plays of which other people were the authors. When do you want to write this thing?"

"We generally—the custom is to have it—in November."

"Very well," I said. "Then I think you'd better begin at once. Shall you do it in Kenilworth, or somewhere else?"

By this time he had regained enough poise to smile deprecatingly.

"I—I thought—in Kenilworth. It might be more—plausible."

"Yes, it might. So you'll want me to ship you now and then some memoranda—suggestions—typewritten—rather lengthy suggestions: say forty thousand words—and you can copy them—I mean compose—in your own handwriting. The first draft, you know, is the best sort of evidence."

"I suppose you—put me down for a good deal of a—well, a four-flusher—"

"Oh, no," I assured him. "This is my regular business; and besides, I'm exceptionally fond of Shakespeare."

He got that one without assistance and apparently liked it.

"All right, Mr. Bacon," he said. "And—the consideration?"

"Five hundred."

"That's reasonable. And you'll start work—"

[illustration]

"'Here! Hold on!' snapped the man in shirt-sleeves. 'Kelly, won't you please remember your character? Shoot some hop into it!'"

I picked up the loose sheets of the great American drama from my desk, and mentally pooh-poohed for the landlord.

"The framework," I said, "you've already completed, and it's mighty good, if I do say so. Therefore, unless you're in a hurry, why don't you outline the characteristics of your probable cast?"

WHEN he left me I had a pretty clear idea of what he wanted.

Within a month we had agreed on the final revision. Throckmorton was working behind locked doors in Kenilworth, and reported that the public was submerged in curiosity. In due course he announced the completion of his play, and invited the cast to a preliminary reading. The crowd was wildly enthusiastic, and in the nick of time some one alleged that such a good comedy deserved a good production. Throckmorton said that if the compliments were sincere, he'd be glad to engage a director at his own expense. His friends yielded to his superior judgment. Throckmorton came down to New York to tell me what had happened. A fortnight later I went up to Kenilworth.

Now during this interval I'd changed a number of my impressions. I'd discovered that Throckmorton wasn't nearly as much of a fool as he looked. To be sure, he suffered from ingrowing plutocracy, and he wasn't topheavy with intellect; but, for all that, he was a pleasant and companionable chap. He was the shyest, most nervous and susceptible young man I'd ever seen; but put him among proper surroundings and he was rather efficient. His house was filled with polo mallets and golf clubs and the hind feet of elephants he'd shot—and, after all, polo trophies and the remains of elephants are about all the evidences of efficiency we have a right to expect in a rich man's house.

I found that in Kenilworth he was considered clever, but reticent. He passed for a retiring genius with a vast amount of brilliancy in refrigeration; and, more than that, he was almost respected by the entire community. I found no trace of doubt that he'd written the play; indeed, I later found some slight resentment that I, an unknown director, should attempt to tamper with an occasional line. It was an interesting condition of things.

Throckmorton put me up at the Inn, and told the proprietor to send the bills to him. The morning after I arrived, he called for me in an automobile, and took me to call on a Miss Embury, who was one of the leads.

"I want you to—well, to talk the thing over with her," he said.

"Don't you think we'd better collect the whole cast?" I asked, "and let me explain some of the basic ideas?"

"No; if you do that, everybody has some objection or other. We three can settle it; then there won't be any appeal."

I didn't grasp the logic of it, but I assumed that this Miss Embury was probably the arbiter of younger Kenilworth, and that Throckmorton knew what he was doing. Anyway, the car curved through some impressive stone posts, and climbed a long hill, and finally stopped before a Georgian mansion of a sort I'd never seen before excepting in the pictorial sections of the Sunday newspapers. We got out, and I made my initial acquaintance with a lay butler. We waited under the shadow of real armor. At length Miss Embury came in.

SHE was a tall, sweet-faced girl, very much restrained. She talked slowly and thoughtfully—I was honestly surprised that such a girl could rise out of such an environment. Throckmorton presented me, and said that we'd come to overrule her arguments, if we could. That was news to me, because I hadn't heard of any arguments.

"I think the play is beautiful!" said Miss Embury. "I'm happy to know that Dick is so gifted. But, truly, I can't approve of it. Can you?"

"Approve of it!" I said. "I think it's a masterpiece!"

Throckmorton was accomplishing marvelous feats with his gloves.

"Tell him what you mean, Margaret," he said.

"It seems to me," said Miss Embury,—she had incredibly big, truthful brown eyes,—"it seems to me not altogether suited for amateurs. Or perhaps I'd better say that it doesn't seem altogether suited to Kenilworth amateurs."

"Don't you like your part?"

"I love it," she said frankly. "It's so near to me, and so like me, that I'm sure Dick must have had me in mind when he wrote it."

"Well, I did," said Throckmorton.

"And yet—it isn't like me, Dick. I'm not so—demonstrative."

"Oh, I see!" said I. "Your criticism is in the way of ethics."

"That's it," said Miss Embury; "the personal element."

Throckmorton threw up his hands.

"And if that's the way she feels about it," he said, "there won't be any play! That's why I brought you here before we met the cast. We've got to—well, thrash out the matter now."

"You could select some one else for my part," said Miss Embury.

"No!" said Throckmorton. "No one else could do it. All we can do is to give it up—"

"The main difference between amateur, and professionals," I interposed, "is this: the amateur is subjective, the professional is objective. I've had—"

"All the others are crazy about it," said Throckmorton disconsolately. "And there's just as much of the personal element in their parts as there is in yours. Of course, it's for charity—but I'm beginning to be sorry I wrote the thing!"

"You mustn't be sorry, Dick."

"It isn't Reynolds, by any chance, it?"

Miss Embury looked at him steadily.

"That's one of the ingredients, Dick."

"Reynolds," said Throckmorton, turning to me, "is the man who was to play the other lead. So there we are. He's the best man for his part, Margaret's the best for hers. Any other way we tried to fix it would be simply a mess. It's too bad that it happens to be your pet charity, Margaret. It means fifteen hundred or two thousand dollars—"

"I'd do a great deal for charity," said Miss Embury, in great seriousness.

"But you wouldn't play with Dixon Reynolds?"

"Not as it's—written," she said.

THERE was a long silence.

"Well," said Throckmorton, "would you play it with any one else?"

"With some one who wouldn't attempt to take advantage of the part," she conceded.

"Tilson," said Throckmorton, "will you do it?"

I was so taken aback that for a moment all I could do was to splutter. Throckmorton was looking at me eagerly and Miss Embury calmly; I began to understand that my host, if he had been born in poverty, might have made a creditable politician.

"Why," I stammered, "if Miss Embury thinks—if that would relieve you—"

"Tilson," said Throckmorton, "is distinctly a professional. You heard him say

Miss Embury looked at me appraisingly. Her eyes, perfectly level and unemotional, disturbed me. I knew that to her society I wasn't of much greater account than a cigar salesman or a chauffeur—but she disturbed me.

"The piece can't very well be rewritten," I said, for relief. "The big motive runs through from the first curtain to the last. It's the main highway—the other parts are subordinate. It's as Miss Embury wishes. If I can substitute for Mr. Reynolds, I'll do it gladly. The other alternatives are to recast or to resign."

"I think," said Miss Embury deliberately, "that under all the circumstances—Dick's play, and it's a wonderful play!—and the charity—and the little time remaining—I should like to have Mr. Tilson take Mr. Reynolds' place."

Throckmorton and I were coasting down the long hill when I asked him point-blank what there was in it for me.

"Well, there's a lot of rehearsals," he said gloomily.

"Man, I realize that! But I didn't come up to Kenilworth to be an actor-manager. It isn't in my line. I'm prob ably the worst actor in the civilized world. Just the same, it entails extra work—and, all else aside, I can't count the pleasure of rehearsing that sickly dialogue with Miss Embury among my tangible assets. That's the system they used at Tarrytown."

"Oh, I'll square it with you at the end," he promised. "Leave it to me."

"Did you have any reason to anticipate Miss Embury's attitude?"

"How could I?"

"True," I said. "We hammered out that part for her, word by word."

Throckmorton grinned.

"We'll make Reynolds assistant stage-manager," he observed; "that'll keep him quiet. And, now that the biggest obstacle is overcome, we can call that general meeting almost any time."

ACCORDINGLY, I put the piece into rehearsal that week. We used the ball-room of Miss Embury's home. Every morning at ten we foregathered to specialize in one situation; every afternoon at three there was a private drill for the more important characters.

It didn't take long for me to recognize that I had to deal with an unusually ambitious outfit. They were a sated, jaded lot with respect to dancing and formal parties; but when the glamour of theatricals flashed in their eyes they were wide-awake and enthusiastic. I had a cast whose parents, taken in the aggregate, rated at approximately nineteen millions—and, for the pranks they played, they might have been school children.

Throckmorton was right—the romance knocked 'em dead! I've been through it time and time again, and they invariably react the same way:

"Don't you think we'd better go off and practise our scene, Mabel?"

Mabel, mighty conscientious: "Oh, yes, Billy."

"All right—let's begin here, where it says 'kiss.'"

Well, they had a wonderful time with it, skylarking around, innocently enough, and they began to be pretty apt, too, at catching an intonation, a gesture. They weren't quick studies,—far from it,—but when they once got their lines they didn't fluff much, and every one of 'em brought in some good interpolations. That was their natural style, you know—repartee, shooting epigrams back and forth—and the local hits! Perhaps you've been in a country town and seen a one-night burlesque. The audience doesn't rise to the local hits half as hard as the aristocracy does—and the amateurs hit harder, too.

But the outstanding feature of those

[illustration]

You couldn't blame a man for having his head turned, could you, when he had to play the part of lover to a leading lady like this?

I asked her once if she were consciously acting, or if she allowed her spontaneity to guide her.

"I forget all about me," she said. "I'm just trying to produce the effect that's wanted. Here I'm supposed to be leading you on—and that's all I think about."

That reply of hers was very enlightening. I saw why she hadn't cared about playing opposite young Mr. Reynolds.

Needless to say, I was painstakingly careful. I never touched her, not even when the script demanded an embrace to render the lines intelligible. I made myself as matter-of-fact as I could. It was diplomatically advisable. But there are two points to remember here: one, that I was young and impressionable; the other, that I'd really written the play. I'd put into the mouth of the leading man my own thoughts, my own phrases. I'd tried to imagine what a girl would have to say to me in order to move me deeply.

REHEARSING with that girl was like reading my autobiography. Sometimes I didn't know whether I was speaking of my own volition, or simply reciting a lesson I'd learned. Some of her lines left me staggering—they were as efficacious as if she'd said them in earnest and alone.

I honestly think it was a good play. At any rate, I was childish enough to be a trifle jealous of Throckmorton when the society columns began to print the opening blurbs. I knew they were blurbs,—I knew they were done by literary blacksmiths who had so many columns to fill every Sunday,—but it galled me to see Throckmorton's photograph in big space, and to read what was said about him. One of the critics who'd damned my Broadway flivver ran up to Kenilworth for a week-end, glanced over the third act, and told me that, if I didn't have too much pride to take pattern by an amateur, I could get more from Throckmorton than I'd ever known myself!

And Throckmorton, although he didn't mean to be offensive, but only to support his prestige, was getting more or less insufferable. He came to every rehearsal; there wasn't a monosyllable, or a cross, or the alteration of the most insignificant bit of business, that he didn't weigh and pass judgment upon. And the gradual assumption of an air of authority deceived me. He slipped so smoothly into control of affairs that, before I knew what had happened, he was the supreme court, and my jurisdiction was nothing more than a nisi prius. Every suggestion I made was referred to him. Finally I was told pretty flatly that I mustn't undertake any changes in the book without his sanction.

Indeed, when the public performance was only a week or two distant, Miss Embury was the only one who recognized my position. She still appealed to me for advice on the finest technicalities; she wouldn't give voice to an immaterial exclamation until she'd had the best instruction I could give her on the shading of it—and after that she'd send it out in her boyish, throaty contralto, so that my pleasure in the work was lost in admiration of her.

I don't mean that I was in love with her; I had too much sense for that. I was well aware that her father paid more for several of his servants than I was earning in a year. But the lines I had originally written for her and revised later—with Throckmorton's consent—had something back of them. So did mine. And although my eyes were open, and I never lost sight of Throckmorton's check at the finish, I'll concede that I was looking forward to that public performance.

THE living-room of the Golf Club was chosen as the auditorium; the advertising was out; the press was invited; the tickets were issued; I had a couple of experts from New York to attend to the make-up; we were set for dress rehearsal.

Throckmorton, as usual, was in command. It was the only time he ever nerved himself to call me down, but he did it then—on my entrance speech. Oh, it was beautifully staged! It was the keynote of the afternoon! Right at the beginning I had my niche; Throckmorton crowded me into it, and sealed it up.

Angry as I was, I appreciated that final stroke of diplomacy. It put me where I belonged—a hired actor, to balance the cast. I could fancy what a roar of derision would go up if, after that, I ever attempted to claim the piece for my own, or to divert any of the credit for the production of it. In its way, it was magnificent!

Throckmorton called me down; I crawled; and the rehearsal went on. The parlor-maid and the butler finished their flirtation; I had two minutes with Miss Embury. We got along nicely; it was nothing but sparring. The action progressed; we came to something more vital.

You can't imagine what a quandary I was in. For weeks I'd put this joyous, kittenish aggregation through their paces. Everybody knew everybody else; there weren't many conventions. I knew that on the last night I should be expected to get in all the business, but I didn't know what on earth to do this afternoon. If I stuck to the stage directions, I ran the risk of being jumped on by Throckmorton, rebuked by Miss Embury, and flayed alive by everybody else. The idea of a miserable barn-stormer (or whatever they thought me) daring to lay a finger upon the sacred person of a distinguished resident, except at the public performance! And yet, if I held to the old order of things, what was the use of a dress rehearsal?

My cue was drawing near; I was on. She was waiting for me. We juggled epigrams; we scored off a bad bridge-player and an unstable horseman. Suddenly she had to say that I never talked seriously, hence I probably never thought seriously. I had to say that I was serious on one topic only. There was a question, and a reply. I took her hand. I was acutely conscious that the atmosphere of the room was oppressive.

"That'll do," said Throckmorton. "You two can handle that scene well enough. Save time. Enter the butler."

I don't know whether I was more disgruntled, or boiling mad at Throckmorton, or disburdened of my worries. Miss Embury and I were looking into each other's eyes, and I was still holding her hand, as we turned to Throckmorton.

"That'll do," he repeated impatiently. "You don't need to—well, to go over all that. It's getting along toward dark. Enter the butler."

SO, when the cast was dismissed,—and I didn't do the dismissing, either,—I went back to the Inn with a resolution. You may believe me or not, but at that moment I said to myself that, when the opportunity came, I wasn't going to be stingy. It wasn't entirely pique—it wasn't altogether my hurt pride: there was some actual sentiment in it.

I respected that girl; and I felt toward her as I imagine a respectable burgher might feel toward his sovereign princess. I said to myself that at the proper contingency we two were going to put over our scenes as they'd never been done before, in Kenilworth or anywhere else. I deduced from her attitude and from her nature, as she'd shown it to me, that when she threw herself into her part in deadly earnest she wouldn't pay much attention to the details. And, like the dreaming idiot that I was, I swore that after the last curtain fell, leaving Miss Embury in my arms down-stage, I'd kiss her again for good measure—and then I'd take Throckmorton's check and throw it in his face, and—I wasn't so certain of the rest of it—go back to the city, and see the only reporter I knew, and give him a story that would make society sit up and take notice.

I went to bed angry, and I got up angry. Sleep had softened me to this extent: I realized that I'd better not talk to that reporter. By lunch-time I wasn't so desperately contemptuous of the check: but the main resolution was fixed and determined, and I waited doggedly for night.

By mid-afternoon I was fairly well convinced that, in spite of the disparity in our stations, I really loved her. I couldn't think of anything else. I sat in my room, living over the lines we had together, creating situations in our normal existence in which those lines would apply.

I'd never before been carried away like

Once I started up: I would go to see her. Then a flash of sanity struck me all in a heap; and I sat down again. What was the use? To her I wasn't even a struggling playwright; I was a fourth-rate actor engaged as a director, and impressed for the sole purpose of banishing an undesirable member of the cast.

I was pacing the room, and looking at my watch every minute or two, when the telephone rang. Throckmorton was on the wire.

"I want you to come and dine with me, old chap," he said. "Just us two. It's—well, it's a preliminary celebration. Will you come?"

I said I would.

"Six o'clock sharp," he warned me. "Don't bother to wear a dinner-coat—wear the suit you're going to use in the play, and that'll let us take an hour and a half for dinner."

"On the dot," I said, and rang off.

I wasn't especially anxious for his company, but it was better than nothing; I was uncommonly nervous.

THROCKMORTON was apparently glad to see me, and he was increasingly affable. We had an excellent dinner, and some of the most luscious sherry I ever met in my life. Over the cigars he began to talk.

"Old man," he said, "very likely you think I've been—well, pretty arbitrary about this play."

"Frankly, I do," I told him.

"Try this liqueur. Well, for reasons that aren't clear to you yet, I had to be."

"Now and then you rather overdid it," I said. "What is this stuff?"

"It's a private brand of my own. Like it?"

"It has an unusual taste. You were saying—"

"I was saying that you'll excuse whatever's happened—after you're in possession of the facts."

"Oh—there is an excuse?"

I felt that he was watching me narrowly. My head was unpleasantly congested. I ascribed it to the powerful emotions of the last few days.

"A good one," he said. "Finish your liqueur, and then—"

"Yes," I said. "And—and—then—"

I'd unaccountably lost all sense of physical adjustment. The walls were rollicking around me, and separating themselves into planes that interweaved and separated again, for all the world like a cubist painting. The table tilted, and I grabbed it, so as not to let it slide away. Throckmorton's strained face was peering over the edge. And that was the last.

When I awoke, my head was aching frightfully. Nervously and mentally, I was demoralized; my brain acted like a gear that's slipping perilously. I was in a strange room, in a strange house. I was lying, fully clothed, on a bed. The effort of rising on one elbow sent me down again in a hurry; but the fresh breeze blowing through an open window was refreshing, and I moved so as to take it into my nostrils.

In a moment I could sit up without nausea. I perceived that it was now quite dark. I got my watch. There was no light of any kind in the room, but a full moon was shining on my pillow. It was half past ten!

DAZED and bewildered, I'd lost the proportion of things. It was half past ten. I didn't know whether it was to-night or to-morrow night; but one impulse was pounding away at my consciousness—I had to get to the Golf Club. It never occurred to me that I was, at the minimum, two hours and a half overdue: I had to get there.

I found that I could navigate, after a fashion. I reeled along the wall until I came to a door, and went out into a huge hallway. I was directly at the top of a flight of stairs; I went down, and then I knew that I was in Throckmorton's house. There was the dining-room. I looked for my hat.

With all my blind rage at Throckmorton, with all my intellect twisted, with all that tremendous and involuntary compulsion to get out, to get away, to get to the Golf Club, I hesitated—because I had no hat. You might say something about that—it ought to interest the high-brows. But thrown carelessly on a chair was a tweed cap; I seized it, opened the great doors, and fled out into the night.

IT was a long mile to the club. I have no recollection of how I got there, or how long it took me. Sometimes I thought I was flying; sometimes I thought I was creeping backwards. But eventually I stumbled up the driveway, up the steps, and into the lobby.

The play was so nearly over that the ticket-takers were inside, enjoying themselves; there was no one to deter me. I blundered headlong into what corresponded to the auditorium, and a good many people in the vicinity said: "Sh-h-h!"

[illustration]

"There was a question, and a reply. I took her hand. 'That'll do,' said Throckmorton. 'You don't need to—well, to go over all that.'"

The room slowly took form; I comprehended the proscenium arch, the stage, the actors. There were two of them—a man and a girl. Their voices came to me, faintly at first, then more and more clearly. Miss Embury was there—it was the last scene! And the man was Throckmorton!

I must have been breathing very hard, because I remember a voice, dim as an echo, saying something about intoxication. That didn't interest me. Miss Embury was gazing up into Throckmorton's eyes, and he was speaking a line I had carefully—oh, so carefully!—revised and rewritten and revamped. And then she was speaking, and the audience was tense.

What was going on? The make-believe, the amateur play, sank into the distance. We were listening to a reality! The audience rose to it in a body. It was unmistakable. I never had a sensation like that one.

"Where is she—the other woman?" gasped Miss Embury. I swear her face went white.

"There never was any other," said Throckmorton. "There never will be."

"But you said you loved—"

"I said I loved my ideal. I didn't know she existed. And then—when I met you—"

"And—all this time—you didn't tell me—"

"I couldn't tell you. I wanted to—I couldn't. The words—aren't there—yet. But if this—will do—"

She was in his arms; he kissed her. I could hear a bell ringing sharply; the curtain dropped on the tableau. The audience was on its feet, yelling itself hoarse. The curtain lifted again; the tableau was unchanged. I doubt if that pair had moved a hair's breadth. I doubt if they would have moved at all, but an enormous sheaf of roses, tossed from the front row, landed exactly between them, and rested upon their arms. It was a bully effect.

Then they eased a trifle apart, and stood looking at each other, so utterly oblivious of the applause, and of the audience, and of everything in the world except themselves, that the cheers doubled and redoubled. I don't know how many calls they took; but at the end they were standing just as before, speechless, while the auditorium rocked in ecstasy, and the man who had written the piece sat silent and unnoticed, with a bedraggled collar, and homicide in his heart.

THE man who took me back to the Inn is still unknown to me. But the next morning I was there in my own room, with only a slight headache, when Throckmorton came in. He squandered no time.

"My dear fellow," he said, "don't say a word! Let me talk to you."

And, since I was so furious I couldn't even articulate, I let him.

And then he told me—told me how he'd been in love with Margaret Embury; how he was too shy, too self-conscious to declare himself; how he had conceived the idea of attracting her through his genius. I had already begun the scenario when he saw further possibilities: he would appeal to her in the words of the piece itself. But for him to take a part at the outset was ridiculous; Kenilworth might credit him with authorship, but everybody knew he couldn't act. So that all his energies were devoted to building up his own prestige, his own glory; and the culmination was to be at the most critical juncture of all—the eventful evening of the performance. The leading man was to be indisposed; Throckmorton was to step into his place and play the part.

His understanding of Miss Embury was the same as mine—he knew that she wasn't capable of being a mere mummer; she would live in her character. He trusted that his own sincerity would carry heavy weight. And he had planned and worked and striven to that single end—that, when she was unsuspecting and without defense, he might speak to her from his heart—in my language—and hear a response from hers. And so it happened.

"And about that dinner," he ended lamely. "I'm frightfully sorry, old chap. I thought of shanghaing you, and all that sort of thing, but it—well, it might have miscarried. You might have bought off the chauffeur, or something. So I thought you'd better be really indisposed. It was nothing but a prescription I got the last time I was in New York—I knew it wouldn't hurt you. And then I dashed over to the club, and said you were ill at my house. You'd have died to see the riot there was! Everybody rushing around, wondering who could play the part. I said I could: I'd attended all the rehearsals; I'd directed things; I'd even directed you. It was the only way out—we took it. It was pretty crude, I know, but—well, here I am. What's the price?"

I began to see the funny side of it.

"The price," I said, "is two thousand."

"What!"

"Five hundred for the play," I said, "five hundred for rehearsing, and a thousand for missing the performance."

"A thousand for—"

"Well," I said. "I'll take your own valuation. I'd have played that last scene, you know."

He brought out his check-book.

"We'll call it three thousand five hundred," said Throckmorton. "And, at that, I call it—well, a bargain."

TILSON paused and rekindled his cigar.

"I'm afraid I can't use it," I said. "It's too melodramatic and impossible."

"The truth generally is," said Tilson. "But, as I told you, it's the only instance I know that bears out your theory."

Into the restaurant sauntered Kelly and Dorothy Dunn. They nodded to Tilson, and sat at an adjoining table.

"What are you having, sweetest?" inquired Kelly languishingly.

"Just a cup of coffee, darling," said Miss Dunn.

"There!" I whispered to Tilson. "Listen to that! Isn't that another instance? Isn't he succumbing?"

"Succumbing!" said Tilson. "What are you talking about? They've been married since 1912! Coming?"

[illustration]

"'The—thing that—limped out there. If it wasn't your trick, it must have been Woodford. His—his cat was with him.'"

By WADSWORTH CAMP

Illustration by Arthur I. Keller

IN reviving "Coward's Fare" in Woodford's Theater, closed for many years, Arthur McHugh appears to be taking chances with the supernatural. Forty years ago Bertrand Woodford died on its stage while playing his favorite rôle in the play, and there is a legend that his jealousy causes his ghost and that of his pet cat to haunt the theater, to prevent any other actor from playing his part. As soon as rehearsals begin there are evidences of some unearthly influence in the old theater. Limping footsteps (Woodford was lame when he died) and those of a cat are heard, and a strange perfume which Dolly Timken, an old actress who played with Woodford, declares he used, is noticeable. Harvey Carlton, the leading man, tells Richard Quaile, who revised "Coward's Fare," that he has received mysterious warnings 'out of the air" not to play the part, but this is not made known, except to McHugh. The first time that the actor, in rehearsal, attempts to read the lines at which Woodford died, Carlton falls dead on the stage. All of the cast, including Barbara Morgan, leading woman, and the new leading man, Tyler Wilkins, show nervousness in rehearsals; and McHugh avoids the big scene in which Woodford and afterward Carlton died. For some reason incomprehensible to Quaile, who is half in love with the girl, the manager is suspicious of his leading woman. He arranges a rehearsal of the principals in the big scene to take place in Miss Morgan's apartment one evening. While they are waiting for Wilkins, who is unaccountably late, the telephone rings with a far-away, ghostly tinkle, and Miss Timken, at McHugh's direction, takes the message. Almost overcome by emotion, the old actress declares she heard Woodford's voice say that Wilkins will not play in the big scene. While McHugh and Quaile are looking for Wilkins at his club, he arrives at Miss Morgan's apartment, and inquires if he is the first to get there. When the two men return, they find Wilkins in a state of bewilderment, unable to account for a space of time that has completely gone out of his life.

McHUGH, frowning and eager, bent over the actor.

"Try to think, Wilkins. You got to remember. There must be something, if you can only remember."

But Wilkins' face remained blank. Even after he had fought for and won a semblance of control, he had nothing more to offer than that statement—beyond the bounds of reason, yet verified by his watch and the clocks—that he had left Quaile's apartment at eight o'clock; had, as far as he knew, come straight; nevertheless had taken an hour and a half to complete the twenty-minute journey. Certainly the man had no purpose in lying.

"That hour's gone out of my life," he said. "It—it makes me feel—sick."

He arose and faced Barbara, while McHugh watched him closely.

"Could I have a glass of water?"

Barbara rang. McHugh continued to study the actor.

The maid slipped in with the water. Wilkins drank it thirstily. He tried to smile; the effort twisted his features unpleasantly.

"Maybe you're suspicious of my habits, Mr. McHugh."

The manager's glance did not waver.

"You say you ate dinner at Quaile's apartment?"

"Yes."

McHugh turned away.

"Must have rotten food at your joint, Quaile, if it puts a man out like that."

He turned to Barbara, whose attitude had been tensely observant—almost, Quaile fancied, apprehensive.

"What's become of Dolly?"

Barbara sighed. At last her hands left the chair-back.

"Dolly was no use," she answered. "We were sure there wouldn't be a rehearsal, and she wanted to go home. She was afraid of the—of the—"

She broke off, glancing at the telephone.

"What's the bluff for?" McHugh asked harshly.

"I don't understand."

"I guess you understand," McHugh said. "Aren't you trying to give me the impression you don't want Wilkins to know about Dolly's scare with the telephone?"

THE protective instinct, to which Quaile had answered before, urged him to interfere; but Barbara gave him no opportunity. Her cheeks flushed.

"Wasn't that your wish?"

"A lot of good my wishes do!" McHugh scoffed. "See here, Barbara. We've come to a show-down, you and me. What you mean by begging Wilkins to throw over the part—talking about madness and suicide? Eh? What's the idea? Time I knew something about it too."

Her tone colored with an anger that failed quite to hide its perturbation.

"You saw Mr. Carlton die. You've more knowledge of what's happened in the theater than I have. You know as well as I do that it does seem mad and suicidal to play that part. If you're too selfish to tell Mr. Wilkins so yourself, I'm not. Well, I've told him."

Quaile, expectant of a riotous outburst on McHugh's side, saw only a growth of the man's determination before this unforeseen defiance.

"I'm the best judge of how to run my own business," he said mildly.

"Then tell me," she answered, "how you happened to overhear what I said to Mr. Wilkins."

McHugh grinned sheepishly.

"Your door was unlocked. I walked in."

"And how did it get unlocked?" she demanded. "You arranged that in order to eavesdrop."

SHE spoke more rapidly—in her eagerness, the words stumbled a trifle:

"It really is time we had a show-down, as you say, Mr. McHugh. You've gone out of your path to be rude and unfair to me. You almost make me believe you suspect me of something. Can't you be honest? What is it?"

"Now come. Now come. I never said I suspected you of anything, Barbara."

"But I know you do," she answered. "After what you've said and done tonight we can't go on together. If my leaving the company puts you to inconvenience, you've only yourself to blame."

The manager laughed shortly.

"Hoity-toity. Come off your high horse, Barbara. 1 never knew you were so darned high-strung. I take water. If I heard anything that wasn't intended for my ears, I'm sorry. Let's forget it."

She hesitated.

"I prefer to drop out. If you're doing this simply because you can't get along without me—"

After that very affecting page of ours "What Men Hate in Women" came out, a number of women called on us; letters poured in; the telephone rang. The consensus of feminine opinion seemed to be that there was more to be said. Far be it from us to begrudge any lady her last word. Here it is.

[photograph]

APROPOS of our hearty indorsement of the style of wife who may be heard caroling over the hot muffins at 7 A.M. every morning—"Huh," said the women-folk, "do you realize what one usually gets for breakfasting with friend husband? The back side of the paper and the cheery burble of the percolator. Print this in your paper: 'Hereafter husbands must either behave chattily at breakfast or take in two morning newspapers.'"

[photograph]

IT'S not the late hours of the "stag racket," or even the little difficulty with the latch-key, that wives mind. It's the terrible insincerity. Every woman knows that each one of these "jolly good fellows" is secretly yearning to be comfortably at home in his slippers. But no man exists brave and unconventional enough to be the first to break away. The law, recognizing this truth, kindly provides a closing time for bar-rooms.

[photograph]

BIG black cigars, shirt-sleeves, and feet on desks were mentioned so many times that we lumped 'em together and here is the dreadful sum total. Yet he seems a pretty good sort of chap, at that. Enjoy yourself, young fellow. The day will dawn when some young woman will get hold of you; turn you round; put both your feet on the floor; remove your cigar; hang up your hat; help you into your coat; and pronounce the finished product "a perfect duck."

[photograph]

NOTHER thing. When the Stick-to-it Gum Company put all those nice little mirrors around stations and things, whom is it supposed they did it for? The female of the species, of course. But does she ever get a look-in? She does not. The reason varies from five to six feet: but there is always a reason.

[photograph]

AND then, the fighting proclivities of the male! In the days of dueling it was the worst. One gentleman would say, "I don't think your wife's hair is naturally curly." "Hah! Mine honor!" gentleman No. 2 would exclaim. "Meet me at dawn beyond the city gates." And if the wife didn't get there, curl-papers and all, in time to prevent it, one of them would kill the other for her sake. Then she would have to take in stairs to scrub by way of supporting the children. And some people actually call men the logical sex!

[photograph]

THIS brave fellow is a good example of another annoying group of males—the philosophic group. When requested to split some kindling, he gets as far along as removing his coat, and then sits down comfortably for an hour or two to estimate how many chickens there will be if they all hatch. Alfred the Great was just like that—let the porridge burn while he was figuring some silly campaign against the Vikings. One just has to keep after them all the time.

[photograph]

WHEN you're inclined to be peevish at the warring nations because her letters to you are "opened by the censor" or your feet are sore from Red Cross dances, stop and think what this country owes to the men and women who have come to it from abroad. Who would have built our railroads if there had been no Italians or Montenegrins? Without Germans, no delicatessen shops; without Austrians like Albin Polasek, no sculpture. Polasek's first work, sent to the Paris Salon when he was an unknown boy, brought him honorable mention. Now, if we ever have another war, you'll see statues of majors by him in every public square in the country.

[photograph]

IT needed Scotch imagination to invent the telephone, and Scotch fight to establish 9,000,000 of them in the United States. For six years after coming to America, Alexander Graham Bell worked in a cellar with tuning-forks, magnets, and batteries, until in his twenty-ninth year he took out a patent for a wire to carry the human voice—the most valuable patent ever issued in this country. After ridicule, through I months when he often had to borrow money for food, after a bitter fight with the Western Union, which controlled wire rights and had $40,000,000 to back it, Bell finally came through victorious. In the first decade of this century his company spent $425,000,000 in improvements.

[photograph]

S. S. McCLURE was nine years old when his mother brought her four boys over from Ireland to give them a chance in a new country. That first winter they lived on frozen potatoes, and his mother washed and ironed by the day in order to keep things going. Young McClure put himself through high school and college, splitting wood, building fires, peddling, teaching school, living part of the time on grapes and soda crackers. At twenty-seven he started the first newspaper syndicate in America—the enterprise which founded his fame as an editor.

[photograph]

AFTER thirteen years in Moss, Norway, Jonas Lie came to sketch the fjords about Wall Street and the cañons under Brooklyn Bridge. Only evenings was he able then to devote to painting, for by day he earned his living in a cotton print factory. At twenty his first painting was accepted by an exposition; but, even then, he had to work in the factory for eight years more before his pictures of snow-covered hillsides, and later his paintings of the Panama Canal, established him as one of our first American artists.

[photograph]

NIKOLA TESLA grew up on the Austrian border, where his father was a Greek clergyman. Finishing school, he secured a job in Budapest as an assistant engineer at $5 per. In 1884 he came to America, and now has many inventions to his credit. His newest idea is that the wars of the future will be entirely fought with machines: automatons looking like men will charge across the battle-field, while the men sit quietly in the corner saloon at home. Hurry along that invention, Nikola; it sounds good to us.

[photograph]

YOU may ride in a 90-horse-power horse-power limousine, and be married to a chorus girl, and suppose that you know something about rapid transit living. But you are only an amateur. You should be married to something that travels 186,000 miles a second. For years Albert Abraham Michaelson, who came to this country from Strelno, Germany, has spent his time fondling rays of light. He knows that the little ray that hits him in the eye this morning left the sun only about ten minutes ago, because the sun is only a trifle of 93,000,000 miles away. On the other hand, if he were living on Neptune it would have to come 2,800,000,000 miles, which is something else again. For all of [?] which knowledge they have pinned the Nobel prize on him.

[photograph]

WHEN Olive Fremstad was four years old she made her first public appearance in Stockholm. In return for her services she was given a chocolate horse, of which she immediately bit off the tail. For this she was soundly spanked and put in a corner. After this bitter experience of fame and its rewards, she came to America and settled down to leading the singing for her father's revival meetings in Minnesota. At seventeen she left home and journeyed alone to New York to study music. Every year one thousand young girls come to New York to study music; but 999 go back home and teach school. Young Olive Fremstad didn't go back—she went right on and on, clear up to the footlights of the Metropolitan.

[photograph]

WLADYSLAW BENDA came over to this country some years after his aunt, Helena Modjeska, greatest of Polish actresses, started her big fruit ranch in southern California, with the dream of making it an agricultural community of Polish refugees. Some of the Poles who emigrated to the Modjeska ranch brought with them pokers and tin pans—necessities they despaired of finding in barbarous America. The community was a failure, but young Benda wasn't; he began to draw black-and-white studies of lovely, languorous Polish ladies—the kind that used to captivate their Russian conquerors, and that now captivated the New York magazine editors to such a degree that Mr. Benda has never been allowed to go back and settle in his native Cracow; instead, he lives immured in a studio somewhere in upper New York City. This is no place to talk shop; otherwise we should mention that our next serial, by James Oliver Curwood, is to be illustrated by Mr. Benda.

[photograph]

IN his youth Abraham Jacobi of Hartum, Westphalia, had a scrap with the Prussian government which landed him in jail for two years, and then made things so hot for him that he fled to England. From there he came to New York. His first year, charging 25 cents for an office call and 50 cents for outside calls, he took in $973.25. To-day, at eighty-six, he holds his place as one of the leading authorities on children's diseases in the country—but don't call him at 12:30 A.M. and expect to get away with a 50-cent piece. Those days are past.

[photograph]

WOULD you like a stomach like a horse? Breathe deep of this ether sponge; zip, zip—two quick strokes of Dr. Carrel's knife; now you may sit up and drink a little orange juice. Your stomach has been removed and a horse's stomach substituted. As a young interne in the hospital at Lyons, France, Dr. Alexis Carrel was obsessed with the idea that worn-out organs of the human body could be replaced with new ones. Years later, at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, he proved it, and has added so much to medical knowledge that the Nobel prize was awarded to him.

[photograph]

IN the afternoon, just before he was scheduled to conduct an evening performance at the Metropolitan Opera House, Dr. Leopold Damrosch died. His son Walter, only twenty years old, took his place. "It can't be done," said the wise ones; "no youngster of twenty can lead at the Metropolitan." But Walter did it. He and his father had worked together in Breslau before. Later on he built up the New York Symphony Orchestra, which means keeping in good humor seventy-five of the longest-haired musicians in the country.

[photograph]