|

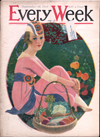

Every Week3¢$100 a YearCopyright, 1917, By the Crowell Publishing Co.© September 10, 1917Gustav Michelson |

By JAMES H. COLLINS

[illustration]

"An advertising man told a merchant he ought to develop the feminine appeal in hardware."

"WHAT is the best way of buying stock for a retail store?"

"What is the correct selling cost for a grocery business of twenty thousand dollars a year?

"What is the right percentage to spend on advertising?"

These are typical questions asked of an efficiency expert by business men seeking information on vital problems in their work as proprietors, managers, and salaried employees. It is easier to ask such questions than to answer them. But the man who asks them shows that he is anxious to improve his methods, and if he can follow the comprehensive answers given him by an efficiency man who goes into the problem in detail, he ought to get even broader information than he expected.

You see, the answers must be general and comparative.

The man who asks such a question believes that somewhere in the world there must be an absolutely correct selling cost or advertising expenditure, and that his business will be more profitable if he can find and follow it.

The efficiency man knows, however, that these things are all relative—not fixed percentages, but constantly shifting ratios, depending on the amount of business done, the season, the times, the human equation in employees and public.

THE inquirer expects a percentage in figures. An honest answer will give him only a ratio, an average, an ideal to strive for.

Instead of a percentage, he gets a batting average. But, if he can follow that, it will take him further than any percentage. For all the results in these matters, and most of the fun, depend on keeping the ratios fluid and shifting—not trying to solidify them into percentages at all.

A hardware merchant had a prosperous business, but had never advertised. The advertising manager of the leading newspaper in his city got him to make special offerings of seasonable goods, developing the feminine appeal in hardware; and results were so good that in six months the hardware man was spending about two per cent. of his gross receipts for space in that newspaper. His interest in advertising was aroused He wanted to know what other merchants in his line spent for advertising. That newspaper was the blue-stocking sheet of the town. Should he use space in the two yellow newspapers? If so, how much?

[illustration]

"A storekeeper who had little money to invest made a point of carrying smart styles to hold the trade."

"How much can a clerk sell in your store?" asked the efficiency man to whom he put these questions.

"Why, that all depends!" said the hardware man, in surprise. "It depends on what sort of a clerk he is, and on the kind of goods he is handling. It depends on the times and the season—even on the weather."

"Well, advertising is the same," answered the efficiency man. "It is just a printed clerk, and will never sell goods at the same percentage twice alike. You pick and watch your clerks, help them with attractive goods, work for good sales averages. Advertising must be bossed the same way, and the proper percentage to spend is all that you can use to increase your turnover, build up patronage, reduce selling costs."

ANOTHER merchant had a general store, with stock divided into half a dozen lines of staple goods—groceries, hardware, clothing, shoes, and so on. He believed that there must be some scheme on which he could arrange his purchase of stock, investing so much money in groceries, so much in clothing, so much in shoes; and that these percentages, once calculated and followed, would automatically make his capital work to better advantage, reduce stale stcck, give him a larger turn-over.

So he took a trip and gathered percentages from other merchants. But, after visiting a dozen stores, he stopped. For he had discovered that there was no "correct" percentage.

One man had fifteen per cent. of his capital invested in the shoe department, but did less business than another merchant who had about five per cent. in that line.

The first merchant just carried so much shoe stock, and let his customers come around when they needed shoes. If they came, perhaps they found nothing that pleased them, and so took the trolley to the nearest city, or sent an order to a mail-order house.

The other merchant, however, had so little money to invest in his shoe business that he had to keep it working; and he carried smart styles that won and held trade.

In groceries it was the same way. The best grocery trade found on his trip was that of a merchant who had hardly twenty per cent. of his money in this department, against from thirty to fifty per cent. in other stores.

Before he left home this investigator believed that he would learn how many of his dollars ought to be assigned to each of his half dozen different departments. When he got back home, he said:

"Here, you dollars! No matter what part of the store you work in, I want you to get busy!"

With selling cost, and practically all other vital items in business, it is just the same. The big department store, with every apparent advantage in capital, stock, employees, location, advertising, may be trying to overcome as high a ratio as thirty or forty per cent.; while the small merchant around the corner, limited in all these resources, has to work so hard and watch everything so closely that he does business on less than twenty per cent.

"What is the best percentage?" can only be answered by asking other questions of the questioner:

"What time do you get down to business every morning?"

"How well do your employees like you?"

"What is the size of your hat?"

WHY does a soldier wear a uniform?

There are some very obvious answers, of course. Men must be able to recognize their comrades at a glance: the rules of warfare prescribe that the men who fight ununiformed may be treated as outlaws instead of as prisoners of war.

But the value of the uniform goes deeper: it has to do with some very elemental principles of psychology.

Our brains are organized by means of what psychologists call the "association of ideas."

Every idea that we have is not isolated from every other idea in our brains, but is so pigeonholed that, when it is called up, it brings with it other ideas that naturally have to do with it.

A certain bit of melody will bring with it a whole train of associated memories. The scent of a flower, a few lines of verse, a certain dress of your wife's—every influence that touches our senses awakes its own particular "reaction."

So the civilian, laying off his business suit, which is associated with all the activities of peace, puts on a uniform, which has always been associated in his mind with courage and obedience and discipline.

And by his very change of clothes he calls up a new stream of associations, which actually help to make him a different man.

Psychologists tell us another thing that is wonderfully interesting. They say that every idea that enters the human mind will immediately produce some kind of physical action, unless it is stopped, or "inhibited," by some stronger idea.

You can prove that from your own experience, as William James shows. Some morning you are lying in bed, thinking of nothing in particular; and suddenly the thought enters your mind that you will be late for breakfast. Before you know it, you have jumped out of bed.

You can not remember "making up your mind" to get up. There was no act of will: simply the idea came, and, finding nothing in your mind to stop it, got itself immediately executed.

A door is open, and you rise and close it. No real decision—just the idea of the open door, and the immediate action brought forth by the idea.

There is a plate of candy on the table, and you put out your hand and take a piece. Or perhaps a stronger idea —the thought that your doctor has forbidden it—comes to you, and your hand stops half way. In either case, there has been no making up of your mind. Simply one idea starting to produce action, and then a stronger idea stopping the action half way.

It is the business of army commanders to build up an atmosphere of ideas that will overcome the ideas of fear and cowardice which are natural to men in battle—to produce what is known as "morale."

So men are put into uniform, and drilled. And the uniform and the drill are constantly sending impulses into the man's mind—constantly saying to him: "You're dressed just like every other man; you must act just like every other man; that's discipline. You're wearing the clothes of courage: you must be courageous."

The uniform helps to make the soldier.

And, in the same sense, clothes help to make the man.

There is a certain rescue mission in an Eastern city. When a man is converted in it, the first thing that they do is to take his shoes and build up the heels.

Because run-down heels constantly telegraph to a man's mind the idea of sloppiness and failure: and if a man is to succeed he must lose those ideas first of all.

Wear uncomfortable clothes, and they set up an irritation that insistently prompts your mind to discomfort and uneasiness. Wear poor clothes, and they produce the idea of avoiding those who have better clothes.

I would have no man a dude, forever thinking of his clothes. Indeed, the ideal is that a man should be so well dressed that he never has to think of his clothes at all.

Comfortably dressed—and so mentally composed. Wearing the clothes associated in his mind with success, and so finding it easier to be successful.

Just as soldiers are put into the clothes associated with courage, that they may find it easier to be courageous.

Bruce Barton, Editor.By HOLWORTHY HALL

Illustrations by

IT must stand as one of the irrefragable axioms of business that a young man just out of college, a young man highly trained in the liberal and useless arts, and wholly ignorant of the commonest commercial principles, is handicapped if he also happens to be sensitive.

And the worst of it was that when Leonard Carter's great-uncle—who was his nearest living relative both in point of genealogy and in the colloquial sense—exerted his influence to get Carter a place in a great wholesale house, he not only admitted that the candidate was abnormally thin-skinned: he also said, in a futile attempt to nullify the weakness, that he was very modest.

Whereupon Mr. Willis, the office manager, grinned and inquired: "Well, what's he ever done to be modest about?"

Mr. Willis had begun as a messenger boy and worked his way to a managership at twenty-nine, and his philosophy had seeped through a fine strainer.

"Anyway," said Carter's great-uncle, who had been one of the most important clients of the house, "give him a chance."

"I'll give him a job," retorted Mr.Willis, with emphasis. "But he'll have to make the chance—and you can tell him not to forget it! No—I'll tell him!"

SO that presently Carter went to work for ten dollars a week; and from June to January his consciousness of inefficiency kept his cheeks flushed until the tints of shame were almost a part of his natural complexion.

Carter was a big, bulky youth, who had been born with many of the gentler attributes of his mother, and all of the physical qualities of his father.

With men of his own age he was at ease, and most companionable; but in the presence of older men he was painfully abashed. For example, he felt toward Mr. Willis almost exactly as he had felt, in his freshman year, toward the coach of the University team. The coach had understood this emotion, and jockeyed Carter into first-string material as a result of it; Mr. Willis, lacking the more delicate perceptions, saw Carter only as a husky, genial, and diligent slow-wit, and unconsciously laughed two thirds of the ambition out of him in six months.

Purely by accident, Carter chose that month of January to fall in love. He had recently been raised to twelve dollars a week; but the minor triumph served only to accentuate his gloom when he recalled that Alice Kingsford's butler got double the money. Nevertheless, he fell tumultuously in love with the daughter of his supreme chief; and for once his self-depreciation had a value. Although Alice wasn't yet in love with Carter, she did like him immensely, and she casually told this to her most persistent suitor, who was Mr. Willis.

Mr. Willis, never remotely considering Carter in the light of a rival, smilingly conceded that he was a very pleasant young fellow.

"And he's certainly a hard worker, too," said Mr. Willis. "There's no doubt whatsoever about that—and it's too bad he hasn't more head. Just the same, I'm going to see that he gets another raise in April."

"Really?" Miss Kingsford was impersonally pleased.

"Up to fifteen," said Mr. Willis.

Miss Kingsford looked at him in vague discomfort. She was without data on the subject of masculine income.

"Fifteen what?" she asked.

"Dollars a week," said Mr. Willis, astonished.

Miss Kingsford gasped.

"Is that all!" Her tone rang like an accusation.

"I call it pretty good progress," said Mr. Willis. "Of course, he isn't a high-grade man, or anywhere near it, but I'm taking his energy into consideration."

"Fifteen dollars a week!" she echoed faintly.

"And before he's been with us a year!" said Mr. Willis. "Why, if he keeps on, and stops making silly blunders, he ought to be getting at least four or five thousand by the time he's thirty. And then he'll marry some nice little girl, and have an apartment up in Harlem, and be ours for life."

MISS KINGSFORD made no further comment, but that evening she asked her father the amount of Mr. Willis's salary, and learned, to her amazement, that it was ten thousand dollars.

"He's a mighty intelligent man," said Alice's father, secretly delighted. "He saves most of his money and buys stock with it. Altogether he must own five or six hundred shares. He's a corner. In another season he'll be a vice-president."

Alice was mentally occupied with a comparison.

"He'll be president some day, then, won't he?"

"Just as soon as I say so," declared Mr. Kingsford.

Alice visualized the big, deferential, impulsive boy who, by virtue of the favor of this paragon, was shortly to be honored by an advancement to fifteen dollars a week.

"Well—when are you going to say so?"

"Oh, that depends," said Mr. Kingsford, smiling meaningly at her.

THERE was one phase of business on which Mr. Willis laid the greatest stress, and that concerned his relationship toward the younger men in the office. Mr. Willis had formulated a diplomatic code intended to combine a certain cameraderie with a certain aloofness; he praised his men briefly but on the slightest provocation; and when it was necessary to reprimand them, his idea wasn't to stun them by heavy blame, but to sting them with raillery.

Carter was super-sensitive. He couldn't endure to be laughed at: he took Mr. Willis's jocular corrections as so many affronts. Also, he was abnormally reserved: lie took Mr. Willis's commendations as so many patronizing familiarities. Firm impartiality was what would have developed his latent powers; instead, he was losing confidence. He became discouraged; he began to loathe Mr. Willis with unlimited loathing.

Carter was gregarious, but he couldn't afford a club, not even the inexpensive local club of his university. So he joined a crack militia regiment. He reacted strongly to the military stimulus and the military discipline. Business was cold-blooded; the Guard was a living inspiration.

Mr. Willis didn't know that Carter was in the Guard; so that it was by pure fortuitousness that he fell into the habit of addressing Carter by military titles. The origin of the jest lay in the appointment of Carter to the duty of marshal in charge of fire drills in the shipping department. In due course the drills were discontinued, but Mr. Willis preserved the memory of them, and even brevetted Carter major. To Carter, who had won his corporal's chevrons within a year, this was galling.

CARTER went to Miss Kingsford, told her exactly what his prospects were, omitting all references to Mr. Willis, and asked her point-blank what were the odds against him. She explained so sweetly and so logically that Carter hadn't a syllable to utter in refutation. She said that she was extremely fond of him, but that the calendar must be the standard of her ultimate decision. Suppose, indeed, that he loved her as no man had ever previously loved, could he conceivably support her? Wouldn't it be much better for them to go on as friends until there were more practical premises for his pleading?

"What I want to know," said Carter, "is if there's a fighting chance? That's all. I know I haven't any right to mortgage your fun for three or four years—I'm not even going to ask you to wait for me. But, as things are now, have I a chance?"

Alice looked at him without affectation or alarm, and nodded.

"As much as any one," she told him.

Carter leaned forward. His expression was suddenly resolute.

"Then will you promise not to believe anything you hear about me before you hear from me about it?"

"Why, what do you mean?"

"Just that. Will you?"

"Surely," she said. "You ought to—"

"The solemnest promise you can make?"

"No; but—what is it, Leonard? You frighten me!"

"I'm sorry," said Carter. "Oh, I'm sorry! But you've promised—and I'm not going to let you forget!"

It was a fortnight before the crisis came.

[illustration]

"'Will you promise not to believe anything you hear about me before you hear from me about it?'"

"Major, I'll ask you to do a job for me, please. Present my compliments to the commandant of the scavenger department, and tell him if he doesn't have this litter cleaned up around my headquarters and police it better from now on, I'll court-martial him!"

Carter started and turned white. He stepped forward, quaking in ungovernable anger.

"You can take your choice," he said under his breath. "You can apologize to me darned quick, or you can have your face smashed. Personally, I hope you don't apologize."

Mr. Willis, who had recoiled sharply, stiffened. He was no physical coward, but he had ethics of his own; and there were a number of reasons, moral, social, and financial, which prevented him from quarreling openly with a junior employee. He laughed, and leaned back against his desk. He was still ignorant of the cause of Carter's explosion; he imagined that it was due to the nature of the errand.

"Calm down, Major, calm down! You're never asked to do anything I haven't—"

"I'll give you ten seconds," said Carter.

Mr. Willis had stopped laughing, but his lips still curled. He was dumfounded and baffled, but he was also sure of himself and of his dignity. He lifted his hand to a bit of mechanism on the wall.

"Take a look at this handle! See? It's a police call. Now go ahead! What's got into you, Carter? You don't think it's worth a trip to the cooler to have the pleasure of assaulting me, do you? Your salary doesn't give you such a devil of a leeway for fines, does it?"

"Come out in the shipping yard, then," said Carter contemptuously.

"You go to the cashier and get your time," said Mr. Willis bluntly. "Understand? Pack up your things and get out of here!"

Carter, who had been seeing queer visions of himself paying ever so dearly for his trifling revenge, shook himself.

"All right. That's your privilege. You've guessed it. It isn't worth the price. But take a hint, Willis—you watch yourself! One of these days—"

"Cut it short!"

"I will. I'm going to get you if it takes a thousand years!"

He wheeled and strode away; and Mr. Willis, suddenly thoughtful, went over and stood at the window.

What perplexed Mr. Willis was what he should do next. He compromised, after some deliberation, on a prompt report to the president.

"It wasn't the personal side of it, Mr. Kingsford," said Mr. Willis in conclusion; "but if he flared up like that, and I didn't jump on him then and there, think what a snarl we'd have got into."

"True, true," agreed the president. "Well—it's too bad. He was a likable young chap. And old Mr. Carter'll be terribly distressed. The unfortunate part of it is that—"

"I know," said Mr. Willis. "He's enjoyed your hospitality; he's been admitted into your house. And that does make it rather a mess. But—"

"It's a very awkward thing," said the president slowly—"an unusually awkward thing. I wish you'd come up pretty soon and talk it over. Come up to-morrow."

ACCORDINGLY, the manager appeared at half past eight, and related his version of the occurrence with such repression that Miss Kingsford couldn't find a flaw in it, notwithstanding the fact that twenty-four hours earlier she had listened to Carter's own account.

"I can't make it out," said Mr. Willis. "I can't make head nor tail of it. I simply told him— Oh, well, there's no use going all over it again. You'd have thought a major's another name for a criminal. But that reminds me, Alice! Some of my old friends are in the Sixth, and they've persuaded me to go along in with 'em. I went through the formalities last night. There's nothing in this rumor of troops to the border, and—"

"What!" said Alice, her eyes sparkling. "Nothing in it! Haven't you heard?"

"Heard what?"

"They're going! Father had a wire from Washington to-day about supplies!"

"No! I wasn't in the office to-day, but—"

"But they are! And the Sixth—why, that's Leonard's regiment!"

"Leonard who? Not Carter!"

"Of course! They promoted him- to a sergeant this morning—he's the youngest sergeant in the regiment!"

Mr. Willis was gulping steadily. There was only one chance in twelve. Still, a horrible intuition was gnawing at him.

"Wha-what company?" he managed.

"He said C."

Mr. Willis relaxed limply.

"That's the company they—they assigned me to!" he said.

On the threshold the Kingsford butler was bowing suavely.

"Beg pardon. Mr. Willis was called on the telephone. He's to ring up the Sixth Regiment armory directly."

From the moment that he realized

[photograph]

NOTHING has impressed me more in reading biography than the fact that men who have no health to begin life with often outlive those who are born with abounding vitality. Mr. Roosevelt was compelled to interrupt his career and retire to his ranch to build up his strength. Both Mr. Wilson and Mr. Hughes at thirty were physically frail.

I wrote to Dr. Lyman Abbott about all this. Those who have seen him on his way to or from his office, or on the platform, will remember that he has looked as if a breath of wind might blow him away. Yet at eighty-two he is still in charge of a weekly magazine, and, in addition, makes numberless public addresses.

"How have you been able to do all this with so slender a store of physical strength?" I asked him; and he answered the question in an article which we publish next week: "How to Be Young at Four-Score."

THE EDITOR.He decided that his manliest and his most creditable course would be to pattern himself after the orderly buckers: to demonstrate to Carter that it was perfectly possible for a man to maintain his self-respect even in a lowly station.

In the meantime Willis promised himself that he would quietly prepare for the worst, and hone for a commission. He had received previous training, and he had a number of influential friends who could pull the wires for him. Thus fortified, Mr. Willis appeared for duty.

As he had anticipated, Carter was in turn thunder-struck at the strange coincidence. As Carter first perceived Mr. Willis, his jaw dropped; and Mr. Willis, seizing the precise second that was most fitted to contain a further shock, saluted stiffly and reported.

The meeting was strictly on official terms; but in the circumstances Mr. Willis wasn't astonished when shortly afterward Carter came to segregate him, and, having drawn him safely aside, addressed him somewhat unsteadily.

"Mr.—er—Willis," said Carter.

"Yes—Sergeant," said Mr. Willis. He had planned to be rigidly respectful, but his ceremoniousness was a trifle exaggerated. Carter reddened.

"I want you," said Carter, speaking slowly, "to apply for your discharge for business reasons. You're only twenty- four hours on the rolls—you can do it now, and maybe you can't later. I'll see that it goes through."

"Thank you—Sergeant," said Mr. Willis, unblinking. "But I think I'll stick."

"Then if you want to be transferred to some other—"

"But I'd rather stay in C Company."

"If we go to the border, and you—"

"Pardon me—Sergeant," said Mr. Willis, "but were not going to the border. That scare's all over. It was newspaper talk. We'll go into camp for a while, and then go home."

"What makes you think that?"

Mr. Willis smiled inwardly at his initial triumph; he had put Carter back in his old niche as one fitted to receive information but not to dispense it.

"I've had private advice from my, Congressman—Sergeant," said Mr. Willis humbly. "We belong to the same club."

"Still," said Carter, without great force, "I think it would be better for both of us if you got your discharge. You could claim business reasons, you know."

Mr. Willis declined politely to embrace a subterfuge.

"But—Sergeant—my business doesn't need- me. It can get along perfectly well without me. No, sir; I'm here, to stay! And I'm not married, and I haven't any dependents."

"Well—" said Carter. "I just want to tell you—you'll get fair treatment, anyway."

"Thank you—Sergeant. I knew that."

"I hope," said Carter, lowering his voice, "I'll treat you as fairly as you'd treat me if the situation were reversed. This private affair of ours can wait."

Mr. Willis was conscious of a momentary chill down his spine.

"Yes—of course."

"That's all," said Carter. "You needn't salute—this time."

THE Sixth went into camp at Van Cortlandt Park, and Alice Kingsford motored out daily, carrying various substances nowhere mentioned in the quartermaster's manual. She was strictly neutral, but Mr. Willis was restive because a sergeant had far greater freedom than a private.

Carter was somehow altering his attitude toward Mr. Willis, an alteration due perhaps to Mr. Willis's unswerving attention to duty. All things considered, Mr. Willis was, in his own opinion, getting along tolerably well. And then, without warning, the Sixth was ordered to the Southwest, and that was a different story.

As soon as Mr. Willis had absorbed the fatal news, he fled precipitately to write his plea for discharge. He swore that he was imperatively needed in the home office; and for his pains he had his own words returned to him. When the Sixth Regiment entrained, Mr. Willis was among those present.

Then Texas; and Mr. Willis, who had once been a jovial tyrant with Carter as his servitor, was now a repairer and a manicurer of highways, with Carter as his foreman. He helped to uproot cactus, and to construct drains; he labored as he had never labored before. He was a composite street-cleaner and policeman.

As his resentment against the system grew, so did his blind resentment against Carter. Their understanding seemed an impossibility. Carter couldn't treat Mr. Willis with any regularity of government; he was afraid to be too strict, and he was afraid that he wouldn't be strict enough.

In the course of a few months Carter, notably competent as far as the rest of his unit was concerned, was thinking of Mr. Willis as his sole bugaboo. Mr. Willis was hectoring him as he had hectored him in the office, but indirectly, subserviently, maddeningly. Mr. Willis had a way of drawling out that title "Sergeant" which made Carter flinch.

MR. WILLIS was adroit, and he was subtle. He also had friends to pull the wires. It was not long before Mr. Willis was abruptly chosen to fill the shoes of a fever-stricken corporal. In this position he had a wider field of operation; and he devoted every minute of his spare time—save those in which he wrote to Alice—to intensive study. And his friends pulled and pulled. There was a miniature upheaval in the regiment, and Mr. Willis added another stripe to his chevrons and threw a dash of vinegar into his communications with Carter.

There was a long interval of political intrigue, and more study on the part of Mr. Willis, and struggling justice on Carter's side. There were dreary examinations and the final tug on the very last of the wires, and, by one of those anomalies that occur even among the best regulated of regulars, Mr. Willis was Lieutenant Willis, and Carter was only top sergeant.

This time it was the lieutenant who sent for Carter.

"Turn about," said Mr. Willis pleasantly, "is fair play. Don't want to transfer, do you?"

"Yes, I do," said Carter wearily.

"Say 'sir,'" reprimanded Mr. Willis mildly. "Say it!"

"Yes, sir," said Carter.

Mr. Willis wasn't offensive, but he had none of Carter's scruples; and he had long been an office manager.

"Always say 'sir' to an officer—Sergeant. Well—I'll see what I can do about it."

Carter looked at him in silence.

"It's more than likely," said Mr. Willis, "that a change can't be made just now. If that's so—well, it isn't a bad company as it stands. I'll do what I can for you. That'll do now. Oh— Sergeant! One moment! Be a little careful, Sergeant! You forgot to salute!"

There were increasingly, trying days on the border—days when the skies opened their sluices and let the water down in solid sheets; and other days when the air itself was thick with a precipitate of alkali. The dispositions of men grew frayed and worn; and the ultra-refinements of civilization went into the discard.

And plodding relentlessly ahead went Carter, tight-lipped and incommunicative, subject once more to the manifest supremacy of Mr. Willis. He hadn't been able to get his transfer. As a lieutenant Mr. Willis was distinctly a martinet. He didn't specialize on Carter, but he wasn't a good officer. He made too much noise and created too much enmity.

Carter was incredibly depressed. It was at about this time that a pragmatic analysis of him would have shown that he had lost the very last vestige of his sensitiveness.

AND when he was at the very lowest depths, he had a tiny note from Alice Kingsford, and the torments of Texas became ridiculously insignificant. Alice was on the way to El Paso; and she wanted Carter to come to see her!

By the greatest good fortune he got three days' leave; and when Alice had been registered at the Paso del Norte for hardly an hour, Carter was walking impatiently about the lobby.

And then she was coming smilingly to meet him, and Carter, with a thousand incoherences in his throat and limitless yearning in his eyes, went toward her.

They were only a pace or two apart when he felt his elbow brushed by some one passing rapidly. The vision of Alice was

[illustration]

"'Why, if he keeps on, he ought to be getting four or five thousand by the time he's thirty. And then he'll marry some nice little girl, and be settled for life.'"

The next moment, when he was shaking hands with Alice and looking ineffable things at her, he was still shaken by the knowledge that Mr. Willis was standing beside them, smiling faintly.

"How's your father?" asked Mr. Willis, disregarding Carter. "How'd he stand the trip?"

"Much better," said Alice. "How did you—" She bit her lip and glanced perplexedly at Carter.

"He telegraphed me this morning," said Mr. Willis. A frown was gathering on his forehead; he was obviously ill at ease.

"Oh!" She cast about her for a trio of chairs. "Let's sit down somewhere and—"

"Er—that is—I'm sorry, Alice," said Mr. Willis, nodding toward the Sergeant. "But—I'm sure you know how it is."

"How what is?" she inquired blankly.

"I'm afraid," said Mr. Willis indulgently, "you don't understand the conventions of the service. Sergeant—"

Carter turned to Alice. He was impossibly angry, but his tone was level.

"He means," said Carter, "that a commissioned officer and a non-com can't sit in a hotel corridor—or even stand here—and talk to the same girl! So, if you'll pardon me—"

"But—why, how ridiculous! I—"

"Until later," said Carter, bowing. "I'll telephone you." And, with the customary leave-taking of a superior officer, he whirled and marched out into the street.

For thirty minutes he walked at top speed, crushing down an insane desire to rush back to the Paso del Norte, to take Mr. Willis by the neck, and to wring it for him once and for all.

CARTER paused on a street corner, and shoved his hands deep into his pockets. His fingers encountered letters, and he remembered that he hadn't yet opened the mail he had received before leaving camp. Indifferently he ripped the flap of one thin envelop, and drew out a single sheet. He read a paragraph, exclaimed aloud, and laughed softly. He stopped laughing then, and gripped the paper tightly and brought it nearer to his eyes. He read it through twice. Then he started in the direction of the Paso del Norte. Twice he came to a standstill and allowed himself to be jostled by passers-by while he read through the document once more.

At the hotel he asked for Miss Kingsford, and, hearing that she was indisposed, he sent up his name to her father, and got a reply to the effect that Mr. Kingsford was in conference and could not be disturbed. Whereupon Carter scribbled a card which he inclosed in an envelop and left for Alice, and went straight out of his precious three days' leave and back to camp, where he sought for and obtained a speedy interview with his captain.

"I know it's practically out of the question, sir," he said; "but if you'll look at this letter— Do you suppose I could get my discharge somehow?"

The captain began to laugh.

"Yes, you can," he said cheerfully. "But not the way you mean. You'll get it about three weeks from next Thursday in our own armory. You'll be mustered out. We just got orders from Washington this afternoon the Sixth is going home." He laughed still more loudly at the expression on Carter's face. "What's the trouble?" he queried.

"Nothing—nothing," said Carter hastily. "Only I wish I'd known it sooner. I wouldn't have wasted so much carfare."

And at that the captain, who had read the greater portion of Carter's letter, laughed most immoderately.

AT the Paso del Norte the next morning Carter was lucky enough to catch the Kingsfords before they had breakfasted. Alice came down first, and as she saw him fretting in his incontinent eagerness, she smiled even as she had smiled yesterday. As he advanced to meet her he was mastered by impulses that stirred him perilously, and shaken by the fear that he had no right to the impulses. And then, just when he was opposite Miss Kingsford, he saw something in her eyes that settled everything.

Heedless of a knot of amused by-standers, they clasped each other's hands and kissed each other as instinctively as if that had been their habitual salutation. They drew apart at arm's length and gazed at each other, and then they both blushed furiously.

"Oh, you're so big and brown and strong!" said Alice irrelevantly. "You scare me! Oh, Leonard!"

"How have you done it?" he demanded with equal irrelevance.

"Done what?"

"Grown so much more lovely!"

Conscious of publicity, Carter hastened to ferret out a secluded spot.

"Alice!" said Carter abruptly. "Alice!"

"You see," she said, as if in explanation. "He wrote lots of letters to me, too—and that's what made me come!"

"His letters made you come?"

She nodded in the affirmative.

"Yes—when I compared them with yours. That's what brought me, Leonard. I'd have come sooner, but father was ill—"

"I hated to run away yesterday—but it was a critical time, dear. And then— Oh, wait! Let me show you!"

He gave her the missive that had so profoundly affected him, and watched her thrill to its contents.

"So," he went on, "I got back to camp as fast as I could to try to get my discharge—and they told me we're ordered. home! We leave in two or three weeks. And after that—"

Alice regarded him rapturously.

"After that—dear?"

Carter told her, palpitating.

"Provided your father approves, of course," he finished.

"I think he will," she hazarded. "He's old and tired—and that was one of the things he came down here to discuss. Only he was going to discuss it with—

[illustration]

"'Turn about,' said Mr. Willis, 'is fair play. Don't want to transfer, do you?' ' Yes, I do,' said Carter wearily."

THE Kingsfords unexpectedly left El Paso, whose climate wasn't agreeing with Mr. Kingsford, for a swing around the Pacific loop; so that Mr. Willis didn't see them again, but he had a long communication from Mr. Kingsford which simply advised him that the matters they had discussed so recently had better be held in abeyance until the Sixth was mustered out of the Federal service and Mr. Willis was at complete leisure. Mr. Willis grinned sagely to himself, and wrote another flaming epistle to Alice.

During these last few days he was extraordinarily kind to Carter. He was really sorry for the man who had so signally failed thrice running—in business, in the army, and in love.

And in due course the Sixth tramped again the pavements of Manhattan, and presently the regiment shouted itself hoarse and shook off the bonds of its oath. And as soon as he was once in citizens' clothes again, Mr. Willis betook himself to the familiar office downtown, and steeled himself for the felicitations.

BUT the congratulations of the staff were somewhat tempered by an excitement that Mr. Willis was slow to analyze. He had put it down as a tribute to his own achievements; but he was rudely awakened when he asked the head bookkeeper if there had been many changes in the force.

"Not exactly in the force," said the head bookkeeper cautiously. "There'll be some in the executive office, though."

"Oh, yes—I know that."

"They say the old man's through."

"Yes—he told me so in El Paso."

"You know who's succeeding him?"

"I don't know officially." Mr. Willis didn't know how much Mr. Kingsford wanted published.

"That so? Well—" And the head bookkeeper became reticent.

Mr. Willis went on to the sales manager, who hailed him with divided interest.

"Hello, Willis! Glad to see you! You're looking great! Lieutenant, aren't you? Good work! Say, wasn't that a scream about young Carter?"

"What's that?" Mr. Willis wasn't informed. "What about him?"

"Good Lord, didn't you know it? All the newspapers had it! Along about a month ago some old fossil—great-uncle, I think—died and left him heaven knows how much money! You remember—the old chap that got him in here. And say, I hear he's engaged to Mr. K's daughter, too! How's that for luck?"

"No!" said Mr. Willis, wide-eyed. "No!"

"Well—that's what they say!"

Mr. Willis proceeded agitatedly to the advertising director.

"Howdy, Willis! Glad you're back! Say—Carter fell in a soft spot, didn't he! Better behave yourself—I understand he's buying out Kingsford!"

"Where'd you hear that?" demanded Mr. Willis in an abnormally dry voice.

"Oh, just talk around the office."

Mr. Willis walked swiftly to the door of the president's office, and knocked. Bidden to enter, he saw Mr. Kingsford and Carter—still in his sergeant's uniform—seated behind the big mahogany desk which for years Mr. Willis had looked upon as certain some day to be his own. Mr. Willis stumbled, and caught himself. There was electric silence in the room.

"Perhaps," said Mr. Kingsford at length, "I'd better leave you two together."

"Thank you," said Carter soberly.

Mr. Kingsford went out.

FOR the space of possibly half a minute Carter drummed on the blotter, while Mr. Willis, sickly white, stared and stared.

"Sit down—please," said Carter.

Mr. Willis, against his will, sat down.

"Willis," Carter said almost inaudibly, "I wish you'd tell me why you always had it in for me."

Mr. Willis shook his head.

"You see," said Carter awkwardly, "I rather liked you—right from the start. I liked the way you acted toward everybody but me. I looked up to you. And then you began to jump on me—"

"You don't need to rub it in," said Mr. Willis, rising. "I know when I'm licked! But I never had it in for you."

Carter had also risen.

"How do you make that out? I don't suppose you'll deny preventing my transfer, will you?"

"That?" Mr. Willis breathed heavily. "Ask the captain. Evidently you haven't."

"No; I took your word for it."

"I recommended it," said Mr. Willis, "but he said you were too good to lose."

Carter's brows lifted sharply.

"Well—when I was here in the office—"

"Never mind," said Mr. Willis. "What's the use? Only you misjudged something—I never insulted you."

"There is some use! You've probably heard a rumor about me and Mr. Kingsford. Well, it's true. I liked this business; I believe in it. I couldn't imagine a better investment. So I'm buying him out. But I don't pretend I'm capable of conducting it—I know I'm not. Now—I suppose you knew our engagement is announced to-day—"

"I—heard of it," said Mr. Willis thickly.

"Well—" Carter looked down at the desk. "Willis, Mr. Kingsford's been talking to me about you. He's told me how many years you've worked here—oh, he told me everything; and I understand pretty well how you must have felt, and—" He stepped quickly from behind the desk, and put his hand on Mr. Willis's shoulder. "Hang it," he said, "I'm not trying to rub it in, Willis—I'm convinced you're a better man than you've ever let me believe, that's all! The point is—are you willing to be president of this outfit?"

Mr. Willis froze to immobility.

"President?"

"That's what I said. Mr. Kingsford's out, and I can't run the plant. I sort of figure that anybody who'd fight against me as you have would fight pretty well for me. Will you begin all over again?"

Mr. Willis's mouth worked queerly.

"You can't mean that."

"I do mean it," said Carter. "Mr. Kingsford thinks you'll be a whirlwind. So do I. Perhaps we'll get along better as equals—that's about the only thing we haven't tried. Call it off, Willis—come on in and begin all over again. Will you?"

Mr. Willis turned sharply away. His thoughts were chaos. This was the house he had hoped to direct; and Carter was offering to insure him of that ambition.

Mr. Willis turned back to Carter, and held out his hand.

"Will you?" he said.

"Certainly." They shook hands.

"I'm with you," said Mr. Willis emphatically, and there was moisture in his eyes. "But—oh, Carter! You didn't need to make it quite so sudden, did you?" He laughed off the moisture, and pulled himself together. "Didn't you realize you'd nine hundred and ninety-nine years to spare?"

By WILLIAM G. SHEPHERD

[photograph]

This French trench fighter was a bag-maker before the war, and not even the prospect of to-morrow's charge can spoil his joy in his new file.

SUGAR is so much a necessity of life that men in the trenches who have been without it for weeks demand it instead of tobacco.

One night, after a sugarless week in Przemysl during the Russian attack on the forts, I said to an Austrian officer, expressing the deepest yearning of my soul:

"I'd give a week of my life for some candy."

"So?" he said simply.

An hour later, in the officers' crowded casino, he took me gently by the arm and said:

"Come with me."

We went out into the pitch-dark streets, and, at the risk of our necks, made our way over the slippery mud-covered sidewalks. We turned into a side street; then into an alley; then into a back yard, and he led me to a door in the rear of a little shop. He knocked gently three times. The door opened, and a timid little woman thrust forth her gray head.

"It's only I, with a friend," said the officer.

"Ah! Come in," said the woman.

It was the kitchen of a little home bakery. One oil-lamp stood on the big brick stove. A dozen officers sat about, chatting.

"Have you bonbons to-night?" asked the officer.

"You see what I have," said the old woman, turning and pointing to a shelf that bore an array of chocolate drops neatly set out in rows on strips of oiled paper.

"Behold!" said the officer to me triumphantly.

All the yearning of a drug fiend for his cocaine was in my soul for sugar.

"You may have only four to-night," said the old woman. "They didn't bring me much sugar to-day."

The officer and I paid thirty cents for four little chocolate drops, and we sat down at the kitchen table with the other officers, to eat them slowly, and to talk as we ate.

WE were breaking a strict military law of Przemysl. The place might have been "pulled" at any time, so the officers told me, and they spoke low, like men in a Kansas "speak-easy."

But human nature was triumphing over the rules of war. Even so simple a thing as the craving for sugar was overriding the wishes and the plans of the Austrian military leaders.

I have sat in a big café in Paris, in days that were dark for the French, when the military teetotal law was almost inexorably strict and when cafés were supposed to be closed at eight o'clock, and seen half a hundred people drinking until early morning.

"Care! Care! Care!" the waiters would say. The proprietor stood around with watchful eyes, ready to rebuke any noisemakers.

It would not be a policeman who would come to the door. It would be a soldier with a rifle, perhaps twenty of them—Gallieni's soldiers, who would drag offenders off to a grim court martial instead of to a police court. But human nature, in Paris, was demanding alcohol, and the love of the Frenchman for his café was not to be overridden by even Gallieni's iron-clad orders.

THE coming of Zeppelins toward London is, by military and naval order, a secret. One of those highly interesting occasions moves somewhat like this:

Guards on the English coast sight a Zeppelin coming over the North Sea. They immediately telephone to their nearest superior, and he, in turn, telephones to his superior in some near-by town. This last official telephones to London, and before long the telephone and telegraph wires are buzzing with the news.

From the aviation headquarters in London go orders to the various aëroplane stations to "take the air" at a cer-fain hour, and to "remain at such-and-such a level." A program of "welcome" is arranged. Civilian guards are called out to their posts. Occasionally messages come in from towns which the Zeppelin has crossed, telling of the movements of the sky-ship.

Moment by moment, the Zeppelin comes nearer to London. An hour or more elapses while the huge menace continues its Londonward journey. In the meantime, in London, civilians are supposed to know nothing of what is going on. They are expected to fulfil their evening engagements in ignorance of the danger. The official mind has decided that what the civilian mind doesn't know won't hurt it.

But human nature has taken hold of things in London. In spite of all the secrecy which the military and naval authorities try to exert in regard to Zeppelin raids, civilians in London do know when Zeppelins are on the way. And who tells them the secret?

The telephone girl, for one. Do you suppose that she can sit there and listen to all this whispering of the coming menace and not let her family and friends know of the danger? Do you suppose, if you have been friendly with her over the line and she has learned to know your voice, that she won't count you in among her friends?

You take the receiver off your telephone, before you start for the theater some evening in good Zeppelin weather, and say to your telephone girl:

"Anything doing this evening?"

She knows what you're asking about.

If a single whisper about Zeppelins has reached her ears, she'll say something that sounds like:

"They're around here somewhere, sir."

If you live in a big hotel like the Savoy or the Cecil, your chamber-maid, your waiter, your valet, your elevator-man, all the good folk who wait on you, will tell you if Zeppelins have been sighted anywhere. It's part of a good hotel servant's job, these days in London, to be able to give the latest Zeppelin news as a portion of his or her service. They get the news from the hotel switchboard.

If you know any clubman in London, just ask him, of an evening, whether the Zeppelins are expected. If they are, he'll know it, because in his club many members are civilian guards, and as soon as a Zeppelin rumor reaches London, they are called out, by telephone, to do patrol duty in the London streets. With the clubman it's a matter of pride to be able to give his friends advance information on Zeppelin rumors.

Human nature has upset all the ironclad orders of officialdom. The telephone girl out of sheer goodness of heart, the hotel servants out of a desire to render remunerative service, and the clubman out of a spirit of pride, have all prepared London for the first big "boom" of the Zeppelin bombs.

During the latest Zeppelin raids in London, everybody, it is safe to say, knew that the Zeppelins were on the way toward London long before they arrived.

HUMAN nature triumphs over the laws and plans of war in the trenches as well as in the capitals of Europe.

At the beginning of the war, when the men had settled down into trenches for the first time, there were so many night raids from one trench to another that white lights were invented which might be fired into the sky to illuminate a large area.

Whenever, in the night, a rifle fire began in one trench, the enemy sent up a white light to discover whether or not the rifle fire meant that a charge was under way. There was, of course, a highly excusable nervousness on both sides, and it was a common occurrence for a trench sentry to fire his rifle at imaginary objects across the way. One rifle shot like this was a signal for all the men in the sentry's trench to .grasp their rifles and fire at random toward the enemy, whether they saw anything or not, on the chance that the enemy had climbed out of his trench and was charging. Then, in the course of time, the following strange arrangement worked out:

If the enemy sent up a white light, it meant that he was not charging. As time went on, these white lights became tacitly a signal which said to the nervous enemy:

"What are you fellows firing for? We're not going to charge. Go on to sleep again, and let us sleep too."

Then the nervous firing would die down, the scare would be over, and quiet would settle down over the trenches again.

Human nature had twisted the meaning of the white light from a question-mark to a declaration-point.

"How good it was to see the Germans send up one of those white lights," said an Englishman to me. "It meant that they were telling us that they weren't planning any devilment."

Men have been executed in this war for giving the enemy less comfort than the English and German soldiers have given each other by the signal of the white light. And yet, there was no way for the military authorities on either side to prevent this form of signaling. Human nature had outwitted them.

WHEREVER I have gone in the Great War, I have seen human nature triumphant. This war, like all wars, is being fought by the rules of human nature.

The great leaders on both sides can not carry the warfare beyond the point where human nature rebels. That is a point which even the great leaders are afraid to approach. With one eye on the enemy, the statesmen and military leaders of both sides must keep the other on their countrymen, to see that none of the rules of human nature are being violated, to see that none of them are even being strained. Violated human nature would rise and rend kings and emperors and overthrow thrones; and the kings and emperors of Europe know it.

This war will end when human nature in Europe will no longer endure it. Which means, in practical talk, when the leaders on one side or the other see that they are straining human nature of their own folk too greatly, and when they become as fearful of the harm their own folk may do to them as they are of what the enemy may do.

The signs are many that this limit is being approached on both sides.

THAT, whatever men may be in business, they are just big boys at home.

That blessed is the woman who is adaptable. Men seldom change; it is practically useless to try and change a husband; better to adjust yourself.

That an older and younger married woman should never live together. Mother and I tried it for several years, with unrest on both sides. Now she is housekeeping in three rooms not too far from me. She is growing younger in enjoying the freedom of her own home, and we love to visit each other.

That it never pays to tell any one your own or your husband's business. If it seems as if you must tell some one, keep a diary.

That it is not fair to ask a husband to do errands. He can not be expected to keep his mind on two businesses—if he is to succeed, he must concentrate on his own.

That fear is one of the greatest home-destroyers. It makes the wife nag the husband for fear he'll be late or catch cold or forget the bills. It makes the mother worry the children with constant admonitions for fear they'll break their necks or tear their clothes. It keeps a woman from a concert or lecture because she is afraid to go out alone; it keeps a husband tied to his wife's apron-strings because she is afraid to stay home alone. Fear is a terrible habit—but it can be cured.

That it pays to take a chance if you are willing to accept the worst it can offer. Fight for the best, if you take a chance; but know that the worst is bearable and will not injure others. Once we took a chance and bought a house oil a very small salary, knowing that if we could not pay for it, we could sell it easily. Several years later we sold it and made money on it. If one does not dare, one will never do.

That marriage need not mean a rest- cure for the brain. Happy is the wife who does not bury her talent. Blessed is the mother who, after the children 'are tucked away, can turn to her writing; her music, or some loved work, and receive refreshment and inspiration. There are nights when her husband must be at the office; there are evenings when he is silent at home. There are dull days, hard times, nervous hours when the only cure is a loved work. Why the married woman should stop studying I do not see. In these days of correspondence schools, evening schools, and special classes, every married woman who feels the need of it should have her own work for which to slave, sacrifice, and study. A. L. L.

"ON the wharves at Archangel are thousands of crates from America, scores of them stenciled in red, 'This side up,' 'Glass,' 'Use no hooks,' 'Handle with care.' Imagine the bewilderment of the moujik longshoreman at such signs! He hasn't the slightest notion what they are all about; so he wields his hook valiantly and tumbles the case upside down, and laughs at the funny tinkle the crate makes inside." And this, says Richardson Wright in The Russians (Frederick A. Stokes Company), is one of the main reasons that the beforehanded German merchants have captured the bulk of trade with Russia. They have been to Russia, and they know what a strange thing is Russian business.

"In dealing with Russian merchants, an American must remember there are methods of business widely differing from his own. The Russian merchant is accustomed to the interminably slow methods of the East, to haggling, and to having a thoroughly good time.

"Enter a Russian bank, for example. You step up to the cash window and present your checks. A bit languidly, the teller receives your papers and asks you to wait. You retire to a corner. Fifteen minutes pass, twenty, half an hour. You step up to the window. The teller and the other clerks are drinking tea and nibbling snacks of luncheon. You go back to your seat, wondering what it is all about. Finally, when tea is over, the matter of your checks is taken up.

"I am often tempted to think that one reason why the Russian merchant is such a poor business man is that he is too fond of enjoying himself.

"There is another way of looking at the same situation. The Russian has learned a salient truth that Americans utterly lack. He believes—and acts accordingly—that it is far more important to make a life than to make a living."

[photograph]

The modern infantryman leaves his training camp pleased with a trim uniform and shining puttees; but in the trenches the only clothing he is particular about is a thick wool helmet and a pair of dry socks.

TO be a member of the bombing squad is an honorable but not an enviable position. Only the very best men in each platoon are chosen.

In Trench War-fare (E. P. Dutton) J. S. Smith tells how an officer must train them.

The first step is to overcome a man's natural fear of the grenade itself. Dummy grenades with fuses attached can be introduced and the men taught to light them, counting the seconds while the fuse burns out. They develop accuracy in throwing. Men should be taught to throw standing, kneeling, prone. It should be known that if a grenade with a time fuse is dropped in the act of throwing, there is time to pick it up and throw it out of the trench before it explodes.

During an attack three grenades per man are issued to each unit of men detailed to open the attack. When out of grenades themselves, the men take over the casualty's; and it is the duty of a casualty, when he is so able, to leave his grenades and ammunition to the care of some other man before "going down."

Here are some of the questions an officer should ask himself when taking over a trench, and keep in mind during his stay:

I am here for two purposes—to do as much damage as possible to the enemy, and to hold my part of the line at all costs. Am I doing everything possible to insure this?

Does every man know his firing position?

Do I do my best to prevent men from exposing themselves?

Have I always got a man ready to take messages to company headquarters?

Are my listening patrols properly detailed?

Have my men always got their gas helmets on their persons?

Am I doing all I can to drain my trenches?

Are the trenches as clean and sanitary as they might be?

Am I doing all I can to prevent my men from getting trench feet? Have they greased their feet before entering the trenches, and have they a pair of spare dry socks?

Are my men drinking water from any but authorized sources?

Do I know the name of every non-commissioned officer and man in my platoon, and do they know mine?

Do my men get sufficient sleep?

THE belief that man can change into animals is as old as life itself, writes Frank Hamel in Human Animals (Frederick A. Stokes Company), a book containing stories and legends from all races.

And because there are so many stories about it, scholars believe that these fables had their origin in spiritual truths.

The prehistoric horse, for instance, instead of hoofs, had hairy fingers separated by membranes; yet, when ancient authors have spoken of men that have been turned into horses because the hoofs bore some resemblance to the hands and feet of man, they have been accused of imposture.

From the Middle Ages have come down countless stories of wer-wolves—men who transformed themselves into wild animals, that they might attack and devour their fellow townsmen.

"Greed, cruelty, and cannibalism are the accusations brought against those who were tried in the Middle Ages for this crime.

"The desire to taste human flesh is a horrible but not improbable reason for the offense. And to superstitious people in the Middle Ages it was an easy thing for a man to impersonate a wild and fearsome animal without necessarily transforming his actual flesh.

"Savage races do not connect the idea of transformation with any thought of evil.

"Thus the Cherokee Indian, when starting on a winter's journey, endeavors by singing and other mimetic actions to identify himself with the wolf, the fox, and other wild animals, of which the feet are regarded by him as impervious to frostbite.

"The words he chants mean, 'I become a real wolf, a real fox, a real deer!'

"Then he gives a long howl to imitate the wolf, or barks like a fox, and paws and scratches the ground.

"Thus he establishes a belief in transformation, and starts forth on his difficult journey in perfect confidence, the power of auto-suggestion aiding him on his way."

A BOOK has been written for the sake of bashful or reticent people who long, secretly, to take a vigorous, clear-voiced, tireless part in polite conversation.

Say you are at a dinner-party. "What author made one hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year by her pen?" you say, breaking into a brief lull in the talk. Immediately the attention of the table is focused on you. The system laid out by the book, which gives One Thousand Literary Questions, is enough to keep even a rapid talker busy for a year of dinners.

The Nation's comment on the book is:

"Here are a thousand enemies of social intercourse marshaled in a solid battalion of boredom. Facts are the death of conversation. They are immodest and blatant. They will not be denied. You're another is their only answer, which at once transfers the struggle into physical realms. Facts awe us. What is more, they are contagious. Their use leads to reprisal.

"If, on mere mention of Dr. Johnson, a Fact-Hun Unexpectedly lands a shell in your conversational dugout, to the effect that 'Dr. J. is supposed to have written 'Rasselas' in a single night to defray the funeral expenses of his mother,' you can silence him with a shower of bombs, true or untrue, about all the other poets who did as much and more for their parents. The only satisfaction in having a fact to utter consists in its being exclusive."

WHEN the Germans came pouring into Belgium,—when, one after another, each Belgian city made its short, wild struggle to stem the tide,—women were much closer to the war than they are now. In A Nurse at the War (McBride Company) Grace McDougall describes the frantic excitement of those days.

"What hurt one most were the evacuations," she writes. "An evacuation means to empty the hospital, and it was done when news came that the Germans were coming very near. Then men's faces would turn white with horror and with fear; women would tremble and turn faint; and we, who had to work, would spend every ounce of our ,strength in dressing those poor fellows—pulling shirts over their shattered bodies, wrapping dressing gowns or coats or what we could round them in their weakness and suffering. We carried them down long stairs on stretchers, even on camp-beds if there were not enough stretchers. We ran downstairs with mattresses, and lifted them off the stretchers on to the mattresses; for we had to take the stretchers to bring down others. And to some of these men each movement meant agony. This used to happen once a week at least! And then, very often, after having been taken to the station on a tram-car, the men would all be brought back, and have to be carried upstairs again and put back to bed."

[photograph]

Here is Grace McDougall in the early days of the war,when Red Cross nurses could really get into the trenches.

Returning to Antwerp one night, after a day of strenuous ambulance work, she had just retired in a hospitable friend's cellar, when the first German shells began to burst over the city.

"That was a terrible night. For two and a half hours we worked carrying men downstairs—the top floor first, with its sixty-nine beds in the corridor, then the second floor, and lastly the fracture wards on the first floor. It was down slowly with a heavy stretcher, and up rapidly with an empty one. I made slings for myself with a bandage, but even then my wrists and legs ached after the first ten men.

"Next day orders came that the wounded were to be moved out of Antwerp. The sick men were packed into 'buses, and, accompanied by the doctors and nurses, joined the great procession of refugees.

"Gradually the night darkened, and the cold became bitter to a degree. I ached with cold and with sitting erect on my little narrow seat.

"One nurse broke into helpless sobbing. She was a brave and splendid woman; but this was our second night without sleep, and the days had been filled with hard work.

"What that night of hell meant to some of the nurses and to the wounded God alone could witness. To me, in the past, war had meant romance and heroic deeds, not the awful hell of agony it is."

WHAT work can crippled soldiers do? What profession can they undertake that will have real dignity and usefulness—that will secure them a decent living?

The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review suggests that a new occupation, dental nursing, be created for the sake of men who have still the use of at least one arm.

A dental nurse would clean people's teeth, scrape them, scour and polish them as a dentist does at the annual visit of his patient. He would perform this service, however, at a price that even poor people could afford. For his profession, unlike that of a dentist, would need only a short, inexpensive training, and inexpensive materials. His work with each patient would last only half an hour.

The world is almost completely ignorant of how much decaying and loosening teeth impair the health. Indigestion, rheumatism, nervousness, and many other of those sicknesses that are always fretting the majority of people can be traced to unsound teeth.

Because dentists are necessarily so expensive, they are quite outside the world of poor people, and the average individual can afford to go only once a year. Consequently, it is generally believed that teeth will decay in spite of us; that it is a rare person who has sound teeth.

"Careful records of teeth that have been cleaned by a dentist once a month regularly for a long period of years show beyond the slightest doubt that the number of cavities that occur are very few, and can be filled when of small size, with little injury to the teeth and with no pain to the patient. The bacteria that cause decay adhere to the surface of the tooth, then cover themselves with a film that is jellylike at first, and if not soon removed becomes a hard covering, under which the bacteria proceed to attack the tooth. 'Decay' follows. Scrape the bacteria off before they attack the tooth, and there is no decay."

The question is raised: Can the dentist afford to give up this branch of his work?

It will bring more rather than less work to the dentist. Barbers were aroused at the popularity of the safety razor. Yet the barber was never more prosperous than he is to-day. Shaving was a luxury in the days of Benjamin Franklin. It is now a necessity for most men. When working-people can afford to have their teeth cleaned by a dental nurse every month, many thousand people will learn to feel concern for their teeth, and will patronize the dentists.

HELEN KELLER, deaf, dumb, and blind, is living a completer and a richer life than most of us. We have the use of all our senses, but we have forgotten the fact. The sense of smell, for instance. Polite people will mention it in relation to perfumery and gardens, but to do so in other instances is not quite nice.

"In my experience, smell is most important," she writes in The World I Live in (Century Company).

[illustration]

Helen Keller's only communication with the outside world is through her sense of touch and of smell.. Yet the world is an unspeakably beautiful place to her.

"I know by smell the kind of house we enter. I have recognized an old-fashioned country house because it has several layers of odors, left by a succession of families, of plants, perfumes, and draperies.

"From exhalations I learn much about people. I often know the work they are engaged in. I can distinguish the carpenter from the iron-worker, the artist from the mason or the chemist. I gain pleasurable ideas of freshness and good taste from the odors of soap, toilet water, clean garments, woolen and silk stuffs, and gloves.

"The dear odors of those I love are so definite that nothing can obliterate them.

"Some people have a vague, unsubstantial odor that floats about, mocking every effort to identify it. Sometimes I meet one who lacks a distinctive person-scent, and I seldom find such a one lively or entertaining. On the other hand, one who has a pungent odor often possesses great vitality and vigor of mind.

"In the odor of young men there is something elemental, as of fire, storm, and salt sea. It pulsates with buoyancy and desire. It suggests all things strong and beautiful and joyous, and gives me a sense of physical happiness. It is not until the age of six or seven that children begin to have perceptible individual odors. These develop and mature along with their mental and bodily powers.

"Without a sense of smell," she concludes, "the objects dear to my hands would become formless, dead things, and I should walk among them as among invisible ghosts."

[photograph]

Sir Richard Dane, a bluff, good-humored Irishman, is employed by China to superintend her tax on salt. This revenue has saved the Republic from bankruptcy.

UNDERSTAND any one thing more thoroughly than does any one else in the world, and your fortune is made. Because Sir Richard Dane knows so well the salt trade in the Orient, he can't even take a vacation. When he resigned his position as Inspector General of the Salt Excise in India, he was not allowed to take a two years' hunting trip in Africa, but had to take charge of the salt administration in China.

So much does the salt revenue mean to the Chinese government that without it the Republic could not have paid the loans that terminated as a result of the war at a critical moment. Sir Richard has increased the yield of this industry in the three years that he has had control from $13,600,000 to $42,000,000 a year.

Every reform in the business has been fought. When one official attempted to send a quantity of salt up the river by steam, the 40,000 people engaged in the junk trade on the Yangtse arose in riot, mobbed him, and forced him to flee for his life. Sir Richard must deal with the prejudices of a hundred million of the most prejudiced persons in the world.

In the old times one half the salt consumed in China was illicit smuggled salt. The boatmen and the carters often made a comfortable living on the side by their smuggling, with the cognizance of the inspectors, of course, who shared the profits. Sir Richard ventured to remove such inspectors, replacing them with responsible men. And instead of many confusing taxes he has introduced one consolidated duty—the salt administration has been placed upon a bookkeeping basis.

The Chinese coolie does not love the new efficiency. He does not love any ordinance that tends to make him work any harder. One can't blame him very much, since, after all, for a day's labor he earns only a place to sleep, one meal, and the equivalent in cash of a cent and two thirds. If it were not, however, for the cheapness of the labor, no company could afford the initial expense of getting the salt.

The salt-wells, often three thousand feet in depth, take from six to twenty years to drill. Ten years is the average length of time before a well becomes a producer.

ALTHOUGH people recognize that public drinking cups are germ-carriers, for some strange reason the dish-washing in restaurants has gone on uninvestigated. Not long ago a number of restaurants in New York City were inspected, and the conclusions of the investigators printed in the American Journal of Public Health.

It was hardly necessary for tests to prove the presence of thousands of bacteria after the dishes had been washed.

The glasses used at the drinking fountains of the average quick-lunch restaurant are not washed at all. After use, they are rinsed off and placed upside down to drain.

The dish-washing process is substantially the same in all places. The dishes are placed in large dish-pans containing warm soap-water, are rubbed with a dishcloth, then rinsed in another dish-pan containing warm water.

There should be a law requiring that all dishes be subjected to water at a temperature of 80 degrees for one minute before they are served to the next patron. In large eating places mechanical dishwashers should be used. Because the dishes are put first into swiftly circulating soap-water, then into boiling clean water several times, then set on edge to dry in the air, they are almost completely sterilized.

PEOPLE who preach birth control are responsible for the widespread idea that large families sap the strength and shorten the life of the mother; that the children of such families are weak and short-lived.

This idea is a mistaken one, according to the Journal of Heredity. It is all right to spread the idea in the slums to poor parents deficient in intelligence, with inferior physique. In that family it would be much better if only a few children were born into it.

But among sound, intelligent stocks, with good physique and average prosperity, the reverse is true. In making a study of the published genealogy of the Hyde family, which flourished before the days of birth control, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell found that, in a normal healthy population, the child with nine brothers and sisters had just about twice as good a chance of living to old age as the child with only a single brother or sister.

This does not mean that a small family must necessarily have weak members; nor that all superior women should bear ten children apiece.

Dr. Bell's message to modern parents is: if you are well enough off, strong and intelligent, and you want a large family, don't be disturbed by the new theory that every child beyond the third is likely to be handicapped. Large families in superior stock will produce superior children.

[photograph]

It is hard to realize that each day has its ship disaster. This boat, submarined near the coast, was lifted up on the rocks by the sea. The black specks are men climbing down by ropes. You can see them in the surf; fighting to get to shore before the ruined hull breaks in two and falls.

By WILLIAM HAMILTON OSBORNE

IN one of the first issues of this magazine we published an article by Mr. Osborne entitled "How to Make Your Will"; and, though two years have passed, we still receive occasional requests for copies of that issue. Here is another legal article by Mr. Osborne that may save a lot of trouble later in the year if you read it before signing the new lease on October first. Mr. Osborne, who is a member of the New York and New Jersey bars, practises law and writes fiction equally well, though which he considers work and which he does for the fun of it we have never been quite able to decide. THE EDITOR.

[illustration]

IN my home town the other day—a city of a quarter million population—the tenant proprietor of a large department-store paid his counsel $3000 for drawing a ten-years' lease of the premises occupied by his Green Store. The tenant paid this, mind you—not the landlord. It is not such a very large store, and it does not cover such a large piece of ground; but it was worth $3000 to the tenant just to have his ten-years' lease drawn right.

Young Mr. Bently Hartshorne didn't pay out any such amount ten years ago to have his lease drawn—he didn't pay a cent. Why should he? Can there be anything simpler than the lease for a little cottage house? Besides, his landlord had one already drawn and ready for him. Mr. Bently Hartshorne signed it. Young Mr. Bently Hartshorne hasn't forgotten the time when he was earning $35 a week and got married on it, and he and young Mrs. Hartshorne moved into the little house on Highland Terrace.

He took the house for a year. At the end of seven months a young man of the name of Smith sued young Mr. Hartshorne for $10,000 damages because he had fallen through Mr. Hartshorne's inside cellar steps. He was the helper on an ice wagon. The steps were pretty rotten—a fact that young Mr. Hartshorne had known for months, and had protested to his landlord about, but without success.

Young Mr. Hartshorne went to his lawyer with the Smith summons and complaint. The lawyer heard the tale.

"Let me see your lease," said the lawyer, evidently dodging all the points that Hartshorne considered most important.

"It's just an ordinary twenty-five-dollar-a-month lease," said the young tenant. "I left it home."

Get it," said his lawyer.

Hartshorne got it. The lawyer looked it over.

"Now," said the lawyer, "under this lease you're bound to make repairs. More than that, if you fail to make repairs, your landlord can sue you for damages—in addition to your rent. More than that, since it was and is your duty to make repairs, you're going to have trouble with this young man Smith who broke his leg."

Young Mr. Hartshorne gulped. "Let me see the lease," he said.

Truth to tell, it was the first time he had really looked it over carefully. He read it through. Then he smiled in pity at his lawyer.

"Why, you boob," he exclaimed, "this lease doesn't say a blooming word about repairs."

"Exactly," returned his lawyer; "and that's just the reason you've got to make 'em. If nothing's said about the repairs, the tenant's bound to make 'em."

"But—but—" spluttered Hartshorne, "I know a dozen fellows—their landlords all make repairs. Why, my landlord made some not three months ago—"

His lawyer twirled his nose-glasses about his fingers, as professional men are wont to do.